Déjà vu in space: ACES atomic clock experiment installed on the ISS

One of the very first commands I sent to the International Space Station (ISS) as a flight controller, many years ago, was to one of our external experiment platforms on Europe's Columbus research module. I don't remember now exactly which experiment it was; whether it was the command to switch something on or the one to activate the 'pin puller' that released the safety bolt used to secure the experiment during its turbulent ride into orbit.

What I do vividly remember is how incredibly nervous I was. I was the least experienced of the three Columbus Operations Controllers during the Space Shuttle mission STS-122. The astronauts were suited up for a spacewalk, but had to wait for our command before they could start work – and back then, our command software was anything but reliable.

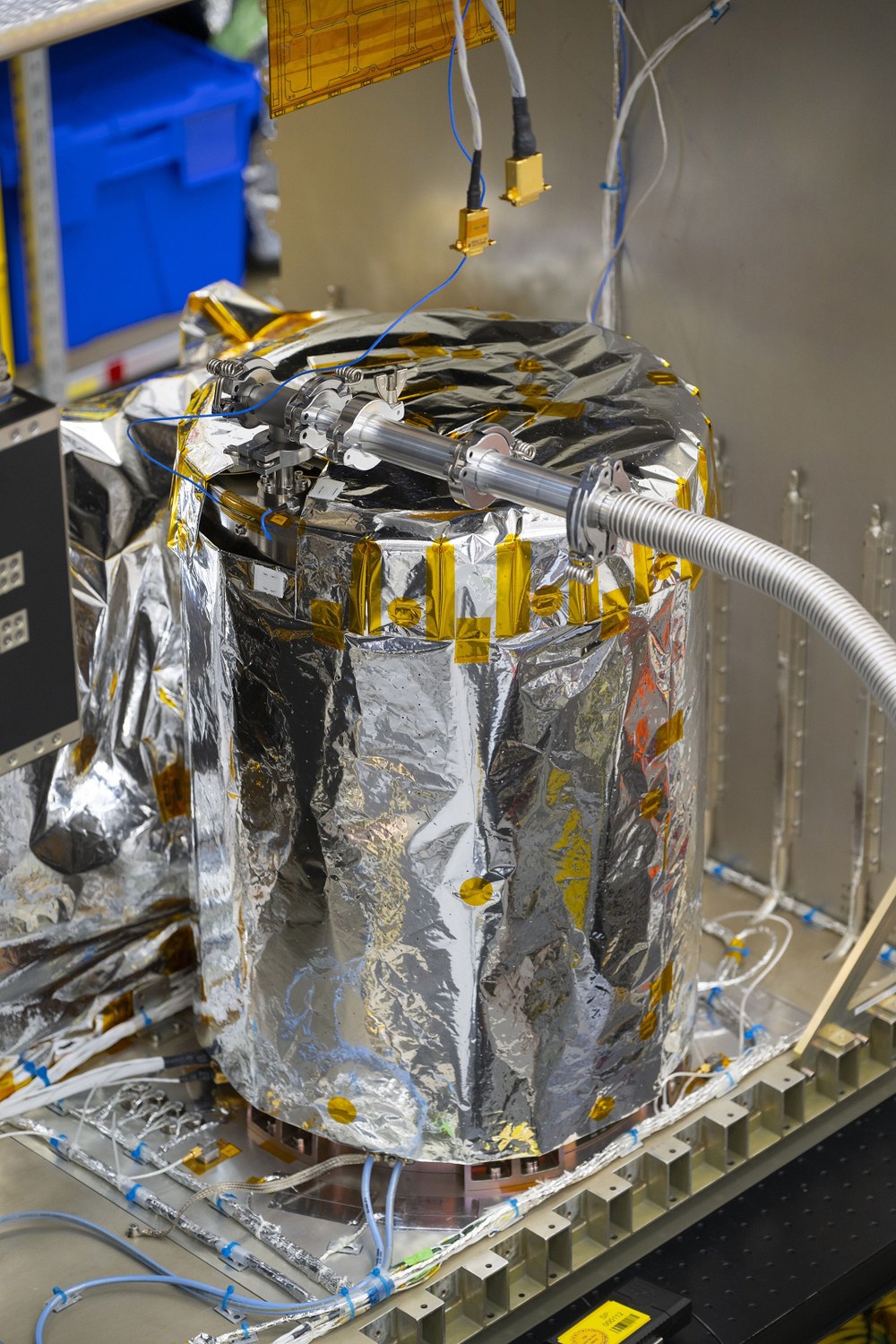

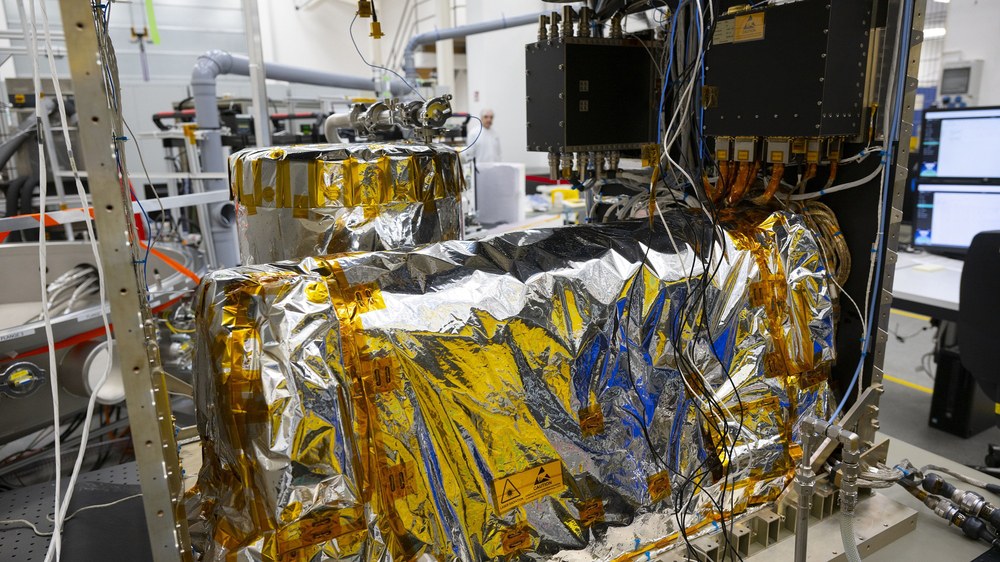

Two new super-precise clocks use atomic vibrations as 'pendulum'

NASA/ESA

ESA / S. Corvaja

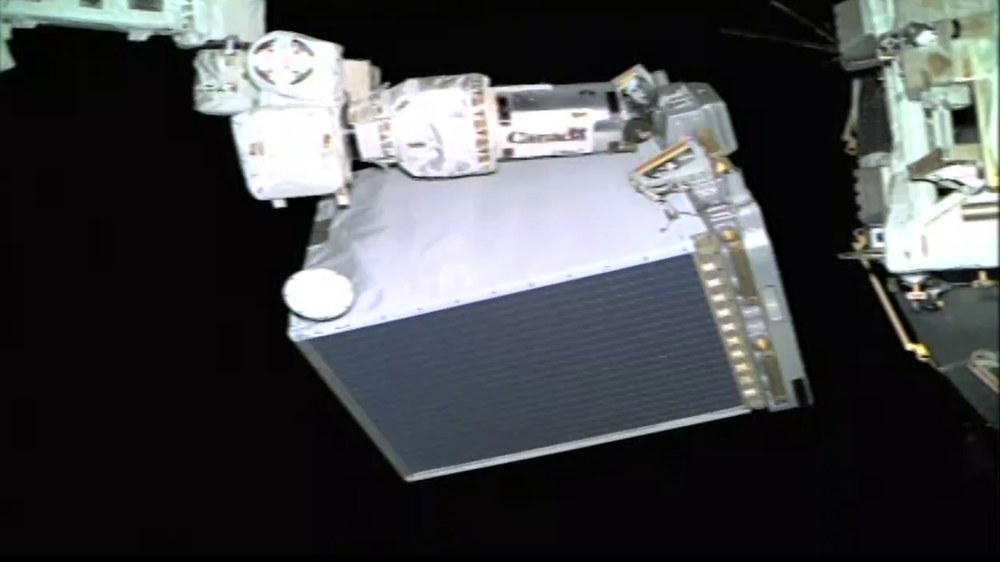

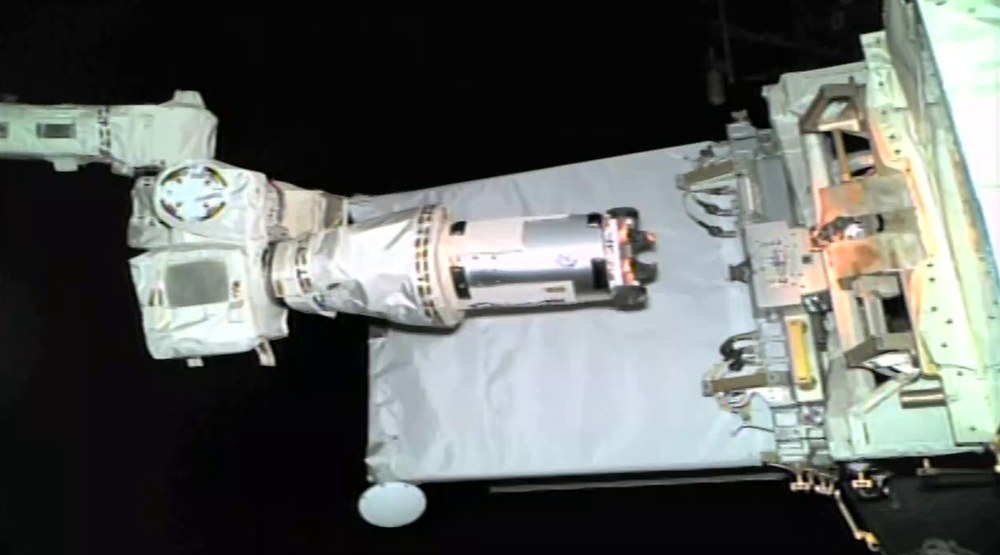

I think back on all this every time I look into the control room this week, because Columbus has once again received a new external payload: ACES, the Atomic Clock Ensemble in Space. The experiment has just arrived at the Space Station on a SpaceX rocket, and it's seriously cool. The package includes two extremely accurate atomic clocks – a caesium fountain clock and a hydrogen maser clock – both of which use the vibration frequency of atoms as a kind of 'pendulum' to determine the time. ACES has two main goals: first, to compare time signals from other, Earth-based, 'super clocks' with unprecedented accuracy. Modern high-tech applications need the most accurate time standards – for internet protocols, satellite navigation, global financial transactions and more.

ESA / S.Corvaja

Second, ACES timekeeping comparisons will allow us to test Einstein's general theory of relativity. I remember – half in horror, half in awe – the complicated tensor equations from my physics studies, which describe how the 'passage of time' depends on the gravitational field in which a clock ticks. Compared to that, the special theory of relativity – where time depends on relative speed of motion – was almost simple. Now, we'll be using 'our' Columbus module to measure these fundamental principles. That's incredibly exciting!

ESA/NASA

Pure stress – the battle against the 'thermal clock'

ESA/NASA

Just like during my first mission, my colleagues are now going through the same phases that I remember so well. First, the power supply must be disconnected. For safety reasons, two independent switches must be opened, one of which is a small lever that the crew onboard the ISS has to flip manually.

Doing this also however cuts off the power to other external payloads, which are then no longer kept warm by the 'survival heaters' out in the freezing vacuum of space. This triggers a 'thermal clock': within a certain time, the installation must be completed and the power restored, or the experiments risk dropping below a critical temperature. You can almost feel the thermal clock ticking as the person responsible – and it's also displayed prominently in the control room because it's so crucial.

ESA / D. Ducros

Then comes the actual installation – this time purely robotic, without astronauts. Finally, the crew onboard is asked to flip the switch again – and then we quickly give the appropriate commands to restore power to the survival heaters and payloads. Only then can a controller breathe a sigh of relief. Having won the battle against the thermal clock, all that remains is to return the experiments to their normal state. With a few commands to the Space Station – and a bit of luck – the 'old' external payloads resume data transmission, along with those newly installed. Despite all the documentation, coordination, reviews and tests, this is the final and ultimate proof that everything really is working.

After his shift, I had a quick chat with Julian, the flight director who oversaw the first activation of ACES. He's very pleased with the result – the installation was successful, and the clocks are 'ticking'. There's still a lot of commissioning work to do in the coming weeks: calibrations, adjustments, system checks. And then, at least in terms of time precision, a new era will dawn for Columbus.

Related links

Tags: