Friday, 07 February – Thursday, 13 February 2020

At Fimbul Ice Shelf

Meanwhile, I am well past the half-way mark of my trip on Agulhas II. The last three weeks have been extremely eventful and thus rich in new experiences. Entries for this blog could be speedily written and it was hard to make the right choice of images from the many at hand. In the past week the ship has been quasi-stationary at Penguin Bukta to unload freight and take on board almost 70 new passengers. So there was enough time to let one's gaze wander past the edge of the East Antarctic ice shelf and over to the West Antarctic.

At Pine Island Glacier near the Amundsen Sea at 101°W and 75°S there was, as has been expected for the past few months, more calving of large masses of ice. At the same place where a large, consolidated iceberg formed in November 2018 the latest Sentinel-1 image shows a mosaic of large and small icebergs. In recent years such calving could be observed at shorter and shorter intervals. It can therefore be assumed that this calving is only another step in the successive collapse of the glacier as it continues its landward retreat.

Somewhat further to the west is the field of rubble from the Thwaites Glacier ice shelf that was captured in a TerraSAR-X recording made on 11 Feb. 2020. Most of the ice shelf disintegrated years ago. What's left is a shelf-ice tongue east of 107°W, but it area is steadily reducing and it will also disappear in the foreseeable future. The TerraSAR-X image was recorded to support the current expedition of the US research ship Nathaniel B. Palmer. It is being used by the scientists on board to plan their activities in the Amundsen Sea, and in combination with Sentinel data and further TerraSAR-X recordings to give detailed indications of the condition of Thwaites Glacier. It and Pine Island Glacier are hotspots of current research projects since their loss of mass contributes to sea level rise already now, and in the future this will be much more the case.

The spatial dimensions of changes like those taking place now on the Amundsen Sea glaciers can be precisely recorded with remote sensing, but cannot really leave a lasting impression of the enormous size of the ice masses. A glance from an Agulhas II window at the breakoff edge of Fimbul Ice Shelf brings together the two-dimensional information from the satellite images with personal impressions of the only apparently everlasting massiveness of the Antarctic ice shelf.

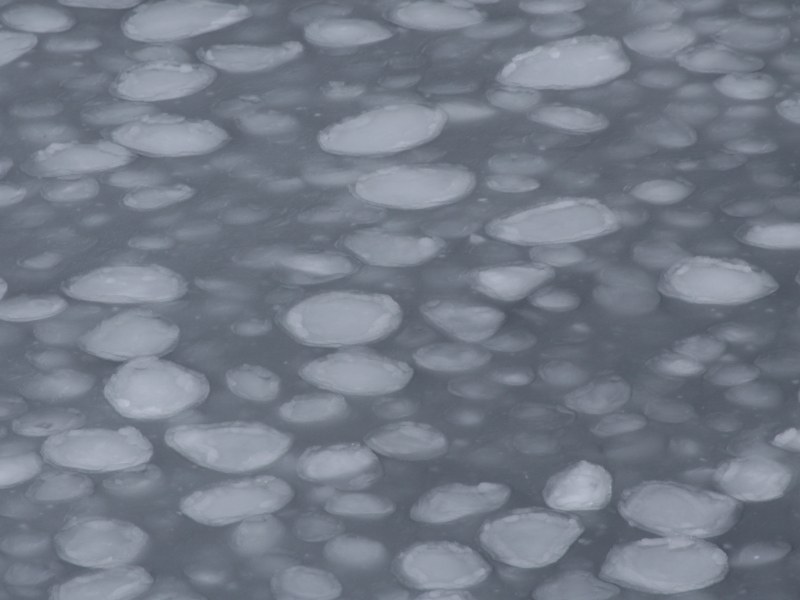

But this blog is not meant to focus only on large ice formations. While Agulhas II was at Penguin Bukta also small-scale phenomena like the formation of so-called "pancake" ice could be observed at close range.

When frozen needles of floating ice stick together because of wave action, ice floes shaped like pancakes can form. Agulhas II crossed through an area with a very young stage of pancake ice on the morning of 13 Feb. 2020 heading westward. On the crest of the bow wave one could nicely see how very thin ice layers are deformed by wave action. A few days before, a field with ideal-type pancake ice had formed. The slightly elevated rims and the round overall shape are evidence of the regular collisions and rubbing together of the pancake ice floes shown here, which are ca. 50 cm in diameter.

It will take a few more weeks before these fragile sea ice forerunners exposed to wind and waves become a continuous ice cover. When temperatures sink again shortly, and especially when polar night begins, sea ice will again firmly enclose the Antarctic continent for a few months. Then it becomes a habitat for penguins and seals, which are at home here also during the winter months. But first they have to wait on the remaining scraps of sea ice left over from the past winter and collect enough reserves of fat for the really cold season!