The history of the DLR site in Berlin-Adlershof

The formation deed of the Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt (German Research Institute for Aviation; DVL), a forerunner of the Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (German Aerospace Center; DLR) was signed in April 1912, following the opening of the second European airfield at Berlin-Johannisthal. DLR had to stop working in Berlin-Adlershof after the end of World War II. The Institute for Cosmos Research (IKF) of the Academy of Sciences of the GDR was established there in 1981. This institute conducted research in the fields of remote sensing of the Earth, extraterrestrial phenomena and, to a lesser extent, material behaviour in microgravity conditions. On 20 April 1990 the IKF and the then German Aerospace Research Institute signed an agreement with the aim of coordinating the work of both institutions. The IKF's expertise in the fields of extraterrestrial physics, spectrometric remote sensing and optoelectronic system development was retained and incorporated into the new structures of the unified German research landscape following the dissolution of the Academy of Sciences in late 1991. The DLR Berlin site was founded on 1 January 1992 with the new Institute of Space Sensor Systems and the Institute of Planetary Exploration. In February 1999, these were combined into one institute, and in 2001 transport was added as a further area of focus for research.

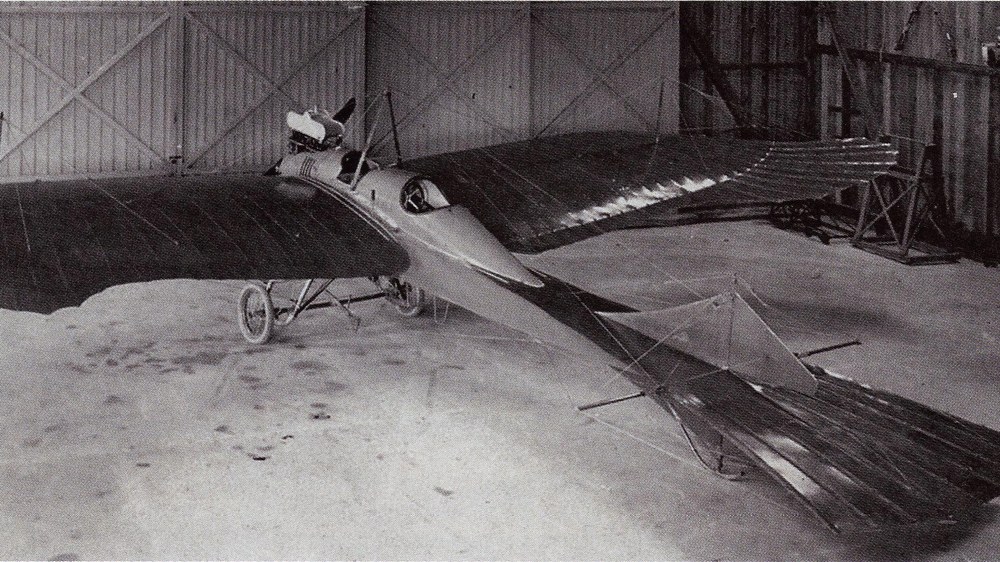

1909

Within a few years of the first successful flights by the now-legendary aviators at the Johannisthal Airfield in southeast Berlin, it was clear that there was a need to support the fledgling art of aviation with scientific research. In fact, back in 1907 Ludwig Prandtl had founded the Motorschiffstudiengesellschaft (Society for the Study of Motor Vessels), one of the organisations that preceded today's DLR. However, did not provide the necessary scientific backing for aviation. At a board meeting of the Deutsches Museum on 28 September 1909 in Munich, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin called for the establishment of a large-scale test institute to promote aviation for the first time.

1910

On 2 March 1910, the German Reichstag resolved to establish the Reich Institute for Airship Travel and Aeronautics. Although this was originally intended for Friedrichshafen, Europe's second airfield in Berlin-Johannisthal was ultimately chosen as the location, and began operations in September 1909.

1911

International Flight Week took place in Berlin on 10–16 May 1910. It was not until 23 May 1911, however, that pilot Alfred Frey thrilled Berliners with a flight that took in the sights of Berlin. After an initial flight, Frey took off again in his biplane at 7:37 am without disclosing his destination. His route took him first to the Britzer Hospital, then to Tempelhofer Feld, along Potsdamer Straße to Potsdamer Platz, via the Tiergarten to the Victory Column, onward to the Reichstag and Brandenburg Gate, Unter den Linden, the Berlin Palace, Oberbaum Bridge, and back to his starting point. News of this flight spread like wildfire. Hundreds of thousands of people poured into the streets. The police lost all semblance of control and traffic ground to a standstill in the city centre. The appearance of an aeroplane over the sea of city houses was completely unprecedented and gave people an inkling of the possibilities of this new branch of technology for the very first time.

1912

The formation deed of the German Research Institute for Aviation (DVL) was signed in April 1912. The first three scientific departments of the DVL – Engines, Aircraft and Aviation Physics – were set up in the spring of 1913. However, the young DVL had to stop its activities upon the outbreak of World War II in 1914 and was only able to resume them in 1922. One of its first tasks was the type inspection of aircraft, including the world’s first all-metal passenger aircraft, the four-seater Junkers F-13. The DVL saw further expansion over the following years, with a small and large wind tunnel, plus the vertical wind tunnel for spinning tests in 1933.

1933

From 1933, the main DVL building was built on the southern part of the airfield site to house the management, administration and technical offices, along with other laboratories and test facilities. The DVL was expanded further in the second half of the 1930s:

- Aircraft construction

- Aircraft engine construction

- Applied aviation

- Administration

The number of staff increased at the same time: by 1940, the DVL had over 2,000 employees. Further large-scale test facilities had been built by the beginning of the World War II. These included a high-speed wind tunnel, the vertical wind tunnel for spinning tests and the low-speed wind tunnel. From 1944 to March 1945, elements of the Adlershof DVL systems and the associated employees were relocated to areas of Germany that appeared to be in less danger. This is how outposts of various DVL institutes ended up in Braunschweig, Munich, Garmisch, Strass, Saulgau and Travemünde. The very last wind tunnel test with an ARADO back-swept wing took place on 24 March 1945.

1941

Konrad Zuse and the DVL. The DVL has long shown interest in computer-aided investigations in flight technology. Konrad Zuse, who was unknown at that time but is now regarded as a pioneer of the computer industry, created his first electro-mechanical computer system, the Z1, in 1938. In 1940 he completed work on his second calculating machine, the Z2. This aroused the interest of Professor Teichmann at the DVL in Berlin. Teichmann hoped that such a machine would help to investigate the issue of wing flutter, as analysis required a great deal of computing effort at that time. Zuse was commissioned by the DVL to construct a programmable computing machine. In 1941, he and a handful of scientists were able to present the fully automatic, program-controlled and freely programmable Z3 computing system. From 1942, Zuse developed the improved Z4, but his work in Berlin was interrupted due to the difficult wartime conditions and Zuse fled Berlin with the new system almost complete. He was able to set up the Z4 with some improvements in 1950 at the ETH Zurich.

1945

When World War II came to an end on 19 April 1945, the DVL had to end its work in Berlin-Adlershof. Most of the existing technical equipment was dismantled and taken to the Soviet Union as part of reparations.

1950

Institutes of the Academy of Sciences of the GDR began setting up on the DVL site in the 1950s. In the spring of 1950, the Heinrich Hertz Institute for Vibration Research (HHI) became the first Academy institute to move into Adlershof. Over time, other institutes and scientific institutions were gradually relocated or newly founded here:

- Institute of Inorganic Chemistry, Mineral Salt Research Division

- Plastics Laboratory

- Institute of Optics and Precision Mechanics (Institute of Optics and Spectroscopy from 1957)

- Institute for Crystal Physics

- Institute of Organic Chemistry

- Crystal Structure Analysis group

1958

The 36-metre radio telescope completed in 1958 became a landmark of the Adlershof research hub. This instrument, which was the second largest in Europe at the time, was used to survey our galaxy for sources of radio radiation. It operated at a wavelength of 54 cm, for which only the telescope dish needed to be swivelled in the meridian plane (known as a transit instrument).

1967

Collaboration between the Academy of Sciences of the GDR and the USSR proved particularly important as part of the governmental-level agreement on the Interkosmos programme signed in 1967. The independent Research Centre for Cosmic Electronics was formed out of the space research-focused divisions of the Heinrich Hertz Institute in 1972 and would become the Institute of Electronics in 1973. This new institute was given the lead role in cosmos research. From 1969 to 1975, GDR researchers were involved in the successful launches of artificial Earth satellites Interkosmos 1 to 4, two large rockets with vertical orbits and four meteorological rockets. For this purpose, the GDR's Scientific Instrumentation Department developed on-board equipment that not only met the specific requirements of the space programme, but also the general criteria for advanced instrument construction. These onboard devices included the infrared Fourier spectrometer (IFS) for remote sensing of the atmosphere and the MKF-6 multispectral camera for remote sensing of the Earth.

1976

The MKF-6 multispectral camera, which was used in 1967 on the Soyuz22 spaceship, delivered images at a flight altitude of 260 km, from which objects on the Earth's surface measuring 10 x 10 metres could be clearly recognised. Besides areas of application in water management, agriculture, geology and mining, this made it possible to create geometrically precise, small-scale state surveying maps much more efficiently than using conventional methods. The infrared Fourier spectrometer in the Meteor 25 weather satellite also had a big practical impact: it was used to measure temperature distribution over the Atlantic and fed into weather forecasts for the Central European region.

1981

The roots of the Institute for Cosmos Research (IKF), founded in 1981, go back to the 1960s, via the Heinrich Hertz Institute, the foundation of which was closely connected to participation in the Interkosmos programme, the Research Centre for Cosmic Electronics and the Institute of Electronics. The scientific profile of the IKF was determined by basic and applied research and technical developments for space travel applications. The research focused on remote sensing of the Earth, extraterrestrial phenomena and material research under space conditions. The IKF also created options for simulating space conditions, in addition to the existing scientific facilities. This meant that the devices and systems designed for use in space could not only be developed and manufactured in Adlershof, but also tested and qualified.

IKF missions and projects:

- Venera

- Phobos

- Altitude research, atmospheric research

1990

In 1990, DLR returned to its roots. Six months after the political changes in the GDR, on 20 April 1990 DLR signed an agreement with the IKF to coordinate the research work of both institutions. On the part of the IKF, this related primarily to extraterrestrial physics and spectrometric remote sensing, but also to the development of optoelectronic sensor systems and the development and testing of payloads for Soviet research rockets. The expansion and operation of the satellite ground station in Neustrelitz was also included in the contract. This meant that the scientific and technical expertise and skills of the former IKF could be retained and introduced into the new structures of the German research landscape.

1992

On 1 January 1992, the new DLR Institute of Space Sensor Systems and the Institute of Planetary Exploration were established at the Berlin-Adlershof site. These were merged into one institute in 1999. Following various structural changes, the Berlin-Adlershof site is now home to the institutes of Planetary Research, Transport Research, Transportation Systems, Vehicle Concepts and Optical Sensor Systems – formerly the Optional Information Systems Facility of the Institute of Robotics and Mechatronics – and the Remote Sensing of Water Department of the Remote Sensing Technology Institute. The site also has outposts in Berlin-Charlottenburg, with the Engine Acoustics Department of the Cologne-based Institute of Propulsion Technology, and in Neustrelitz, where researchers work on communication, navigation and Earth observation. Neustrelitz has been an independent DLR site since 2008.

2001

In January 2001, research at the site was expanded to include transport. As pioneers in environmentally and socially responsible transport system and management, the work of the scientists and engineers is primarily geared towards cross-modal concepts and the use of the very latest technology for transport. The Institute of Transport Research and the Institute of Transportation Systems (formerly Transport Management and Vehicle Control Systems) conduct research into transport from Adlershof.

2002

School's out! Into the lab! Since the summer of 2002, the DLR_School_Lab Berlin has been inviting middle and high school students to engage in hands-on experiments. Under the expert guidance of experienced instructors, children and young people can become researchers by independently conducting exciting experiments related to current site-specific research topics.

2017

Today, DLR Berlin-Adlershof is involved in all of the leading missions in our solar system; Cassini-Huygens to Saturn, Galileo to Jupiter and its moons, the Rosetta comet mission, and CoRoT and PLATO, which are searching for extrasolar planets. Scientists from the site have made a major contribution towards the mission to the Red Planet in the form of the high-resolution stereo camera (HRSC) on the Mars Express. Meanwhile, the 'flying fire detector' and BIRD technology carrier, which was brought into orbit in October 2001, is the first infrared satellite for fire detection from space. The follow-up mission, FireBIRD, uses the two small satellites – TET-1 (launched in 2012) and BIROS (launched in 2016) – to track down forest fires on Earth. And the Adlershof scientists aren’t just involved in the planning and preparation of space missions, but also in the processing and evaluation of the scientific results.