Space research assists humanitarian aid efforts on Earth

- Technology such as DLR's mobile, deployable plant cultivation unit, MEPA, and vehicle control systems could also be deployed in crisis regions.

- WFP and DLR have been close partners since 2019.

- This year, WFP won the Nobel Peace Prize.

- Focus: Space, transport, robotics, digitalisation

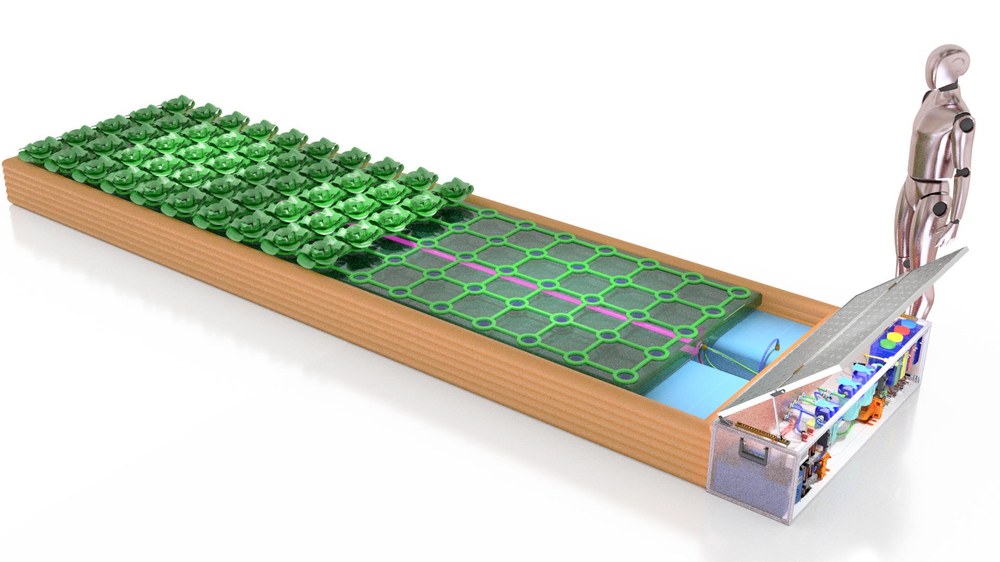

New technologies are in great demand for alleviating hunger around the world, providing rapid relief in disaster situations and achieving sustainability goals. Many of these new technologies, such as the deployable plant cultivation unit MEPA (Mobil Entfaltbare PflanzenAnbaueinheit) developed by the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR), come directly from space research. In addition to supplying astronauts in space with a supply of tomatoes and lettuce, the technology behind MEPA could also be used in the future to provide food for people in crisis regions who have lost their primary source of nutrition. Similarly, the control systems that allow a rover to navigate the rough terrain of Mars are also suitable for the small transport vehicles that the UN World Food Programme (WFP) uses to distribute relief supplies. This year, DLR has been working with WFP to launch a project to help ensure that aid supplies can be delivered to places where it is too dangerous for human drivers to venture.

DLR has been working with WFP for two decades. In early 2019, they established a formal partnership that aims to more closely integrate humanitarian aid and technological innovations. This year, WFP won the Nobel Peace Prize.

"We would like to congratulate our long-term partner on this remarkable award," announced Anke Kaysser-Pyzalla, Chair of the DLR Executive Board. "The German Aerospace Center is proud to be able to support the vital work of the World Food Programme with its extensive experience in research and technology development."

David Beasley, Executive Director of the World Food Programme, likewise expressed his gratitude for DLR's contribution to WFP's life-changing and life-saving missions, adding: "WFP's long-standing cooperation with DLR over the last 20 years has been of immense value to our operations."

With its Humanitarian Technologies project, an initiative launched by Hansjörg Dittus, Member of the DLR Executive Board for Space Research and Technology, DLR is acknowledging its responsibility to address global and societal changes. Approximately six million euros of funding will be allocated to facilitating the transfer of the results of space research projects into humanitarian applications. This will include, for example, investigating how geoinformation obtained by satellites can be processed in such a way as to grant aid workers a quick situational overview, and determining how artificial intelligence can be used in disaster management. DLR remote sensing data can also help to document the effects of climate change or detect crop failures. "With this initiative, DLR is fulfilling its social responsibility to translate its research in areas such as the space sector into humanitarian applications that are both low cost and adapted to the needs of aid organisations," explains Dittus.

The UN World Food Programme provided food support to nearly 100 million people in 88 countries in 2019 alone. Dominik Heinrich, Director of Innovation at WFP, reports on his work and WFP’s collaboration with DLR in the following interview.

©WFP/Rein Skullerud

Mr Heinrich, as Director of Innovation at WFP, you focus on change and new projects. In other words, you primarily concern yourself with the future. What do you see there?

To achieve zero hunger by 2030, we must innovate and embrace new technologies. Due to conflicts and climate change, hunger is on the rise. Organisations on the front lines, such as WFP, are being forced to do more with less every day. Advances in mobile technology, big data and artificial intelligence have the potential to help WFP fulfil its ambitious mission more effectively and efficiently, transforming the lives of vulnerable people across the world. WFP builds practical, needs-based digital solutions to help attain the Sustainable Development Goals at scale, drawing from a legacy of innovation in field operations.

In all 88 countries where WFP works, it has innovated, finding new ways to reach and serve the furthest behind in challenging environments. In the 1990s WFP deployed email over radio, in the 2000s it started distributing aid through e-vouchers, today it carries out field assessments with drones and mobile technology. Today, WFP's digital transformation is about embracing technology and data to enhance the efficiency, accountability and impact of our work: providing food assistance to over 97 million people worldwide. WFP puts the needs of the people we serve front and centre, applying digital solutions and the smart use of data to save lives and change lives.

How important is WFP’s collaboration with research institutions?

Our solid partnerships enable us to experiment and adapt cutting-edge technologies to strengthen food systems, shorten humanitarian response times, deliver assistance more efficiently and make funds stretch further. WFP partners with numerous universities and academic institutes. Collaboration with research institutions, especially those like DLR, with which WFP shares common values, is tremendously important as it contributes greatly to the resonance and impact of innovations to help the most vulnerable.

What are you looking for from DLR?

At the beginning of this collaboration, DLR provided support in satellite imagery for emergency response, risk mapping and early detection of climate developments to help inform preparedness and response measures. More recently, we have collaborated with DLR on AHEAD (Autonomous Humanitarian Emergency Aid Devices) to develop tele-operated, all-terrain vehicles to safely deliver food and humanitarian supplies in the difficult last mile.

DLR has already demonstrated leadership in bringing technology and innovation into the humanitarian world. In the future, it would be great to expand our cooperation in areas of mutual interest, including Earth observation technologies, artificial intelligence, autonomous vehicles, data science and others. I also look forward to seeing some of the projects we have launched recently go beyond the pilot phase and reach scale.

You previously worked for WFP in Lebanon. What is WFP’s most urgent task at the moment?

Famine is once again threatening the world and all four countries at risk are conflict-affected: Yemen, South Sudan, the north-east of Nigeria and Burkina Faso. Famine usually only occurs in cases where humanitarian access is blocked. WFP’s food assistance has in recent years nearly always been successful in preventing populations from falling into famine. Early action has saved millions of lives over the decades – in many cases multiple times in the same countries.

WFP needs 15 billion dollars in 2021. 5 billion dollars of that is required just to avert famine and the remaining 10 billion dollars to support the rest of our work. WFP is uniquely positioned to fight hunger in more than 80 countries.

By identifying which innovations and technologies will be most effective, then scaling them up responsibly, WFP can address famine more quickly, efficiently and cost-effectively, stretching resources, strengthening accountability and serving as many people as possible.