Low-altitude flight over dwarf planet Ceres

Currently just 385 kilometres away from the surface, the Dawn spacecraft is orbiting Ceres and acquiring images that show the dwarf planet at an unprecedented resolution of just 35 metres per pixel. These images allow scientists to look at a surface strewn with craters, fractures, domes and bright areas. "Ceres contains a fairly substantial proportion of ice and is therefore an extremely dynamic celestial body, which is what makes this dwarf planet so exciting," explains Ralf Jaumann, a planetary researcher at the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) Institute of Planetary Research and a member of the Dawn mission team. Dawn has been in its Low-Altitude Mapping Orbit (LAMO) around Ceres since December 2015. "Entirely different kinds of crater are found on the dwarf planet. In places, the surface is also smooth and covered by a mysterious light-coloured material… So there are still plenty of unanswered questions for us as planetary researchers."

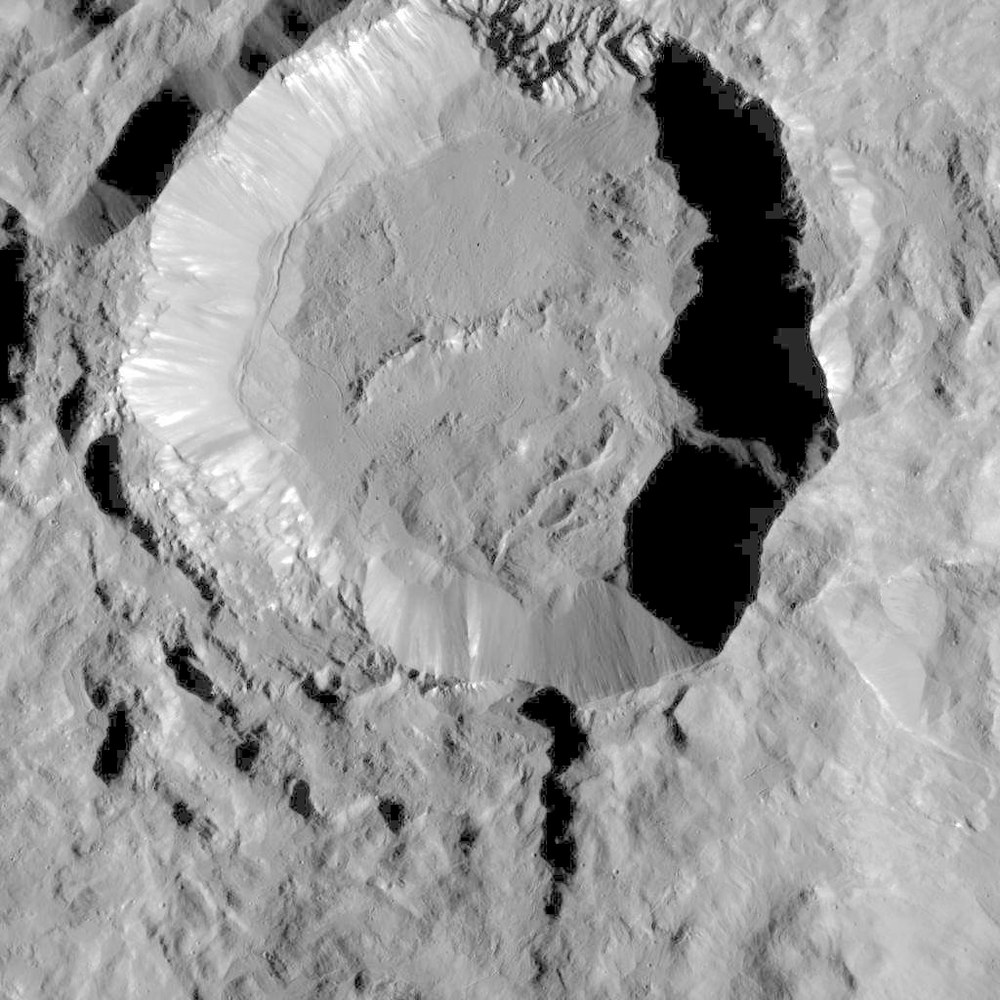

Crater filler with smooth content

Kupalo Crater is a source of this type of question. Originally formed by the collision of another body with the planet, 26-kilometre diameter crater is filled with a material that creates a flat plain within the crater rim. "Kupalo is among the more interesting areas, as a layer of material accumulated later on, covering the crater floor," says Jaumann. "The material in the interior of the crater must obviously be younger than the crater itself." It is likely that the crater is more than two kilometres deep, but it is over half-full with fine material. Now, the crater rim appears to rise just 1000 metres above its interior. There is a certain amount of controversy between the scientists participating in the mission concerning the origin of this material. "It might be material formed by melting processes following the impact, but it could also have come from inside Ceres itself."

There are also several possible explanations for the bright stripes on the crater rim: "They may be salt deposits or even ice," explains Jaumann. "Alternatively, they could be indicative of particularly reflective, smooth surfaces – and the Sun is playing a trick on us." But this response simply makes the Kupalo crater a perfect example of the question that interests the scientists involved – are the unusually bright areas salt deposits or ice?

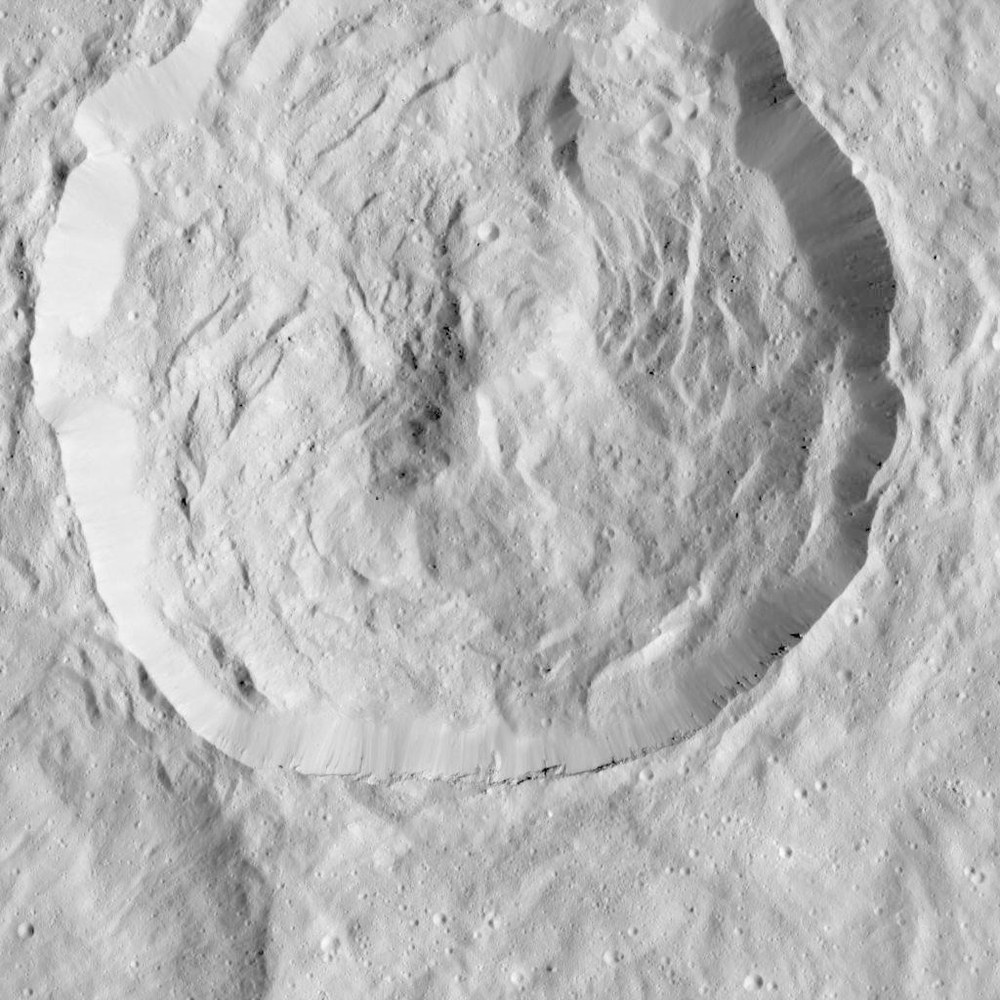

Fissures and bright areas

These bright areas are also clearly visible on the base of Dantu Crater. With a diameter of 126 kilometres, this crater is strewn with depressions and fractures and also shows the bright areas that surprised scientists during the approach to Ceres. "Whatever we are seeing there, it is certainly fairly recent; the brightness clearly indicates that cosmic radiation has not yet altered the material to any significant extent." Only the colour and spectral images that Dawn will acquire over the course of the mission will be able to determine whether they are indeed salt or ice deposits. The fissures, which in some cases expand in a radial direction from one central source, could be the result of uparching processes.

Rolling hills in a crater

Messor is an older impact crater; other impacts have occurred repeatedly since its formation, creating numerous additional craters both in its interior and nearby. "The mountains inside the crater were produced by landslides building up in overlapping layers of material." As a result, the slides have now assumed a wave-shaped pattern. "What we see now are rolling expanses of hills," says Jaumann, describing the unusual shapes. A similar picture can be observed in a currently unnamed crater: "A great amount of material has accumulated in the crater, indicating that large, separate blocks of material have slipped into the interior from the rim."

3D model in preparation

Dawn's orbits around the dwarf planet Ceres are allowing the production of the first complete image of its entire surface from an altitude of 385 kilometres. But DLR will require additional images to continue preparing the three-dimensional elevation model of Ceres using higher resolution data. The Framing Camera system will image the surface of the celestial body from various angles during these orbits. This task will have been completed by summer 2016. The planned inclusion of colour and spectral data will help to solve mysteries such as the nature of the bright areas and their origin.

A mission of opposites

Ceres is the second celestial body to be analysed during the course of the Dawn mission. Planetary researchers examined the rocky asteroid Vesta from July 2011 to September 2012. The mission has been investigating the former asteroid Ceres – elevated to the new status of dwarf planet in 2006 – since March 2015. "They are both exciting in their own different ways; Vesta is a 'dry' asteroid made of rock, while Ceres as a 'wet' asteroid with a high ice content. These are two completely different worlds that have undergone altogether dissimilar development processes.

Dawn is expected to remain in orbit around Ceres at a distance of 385 kilometres until the end of June 2016. The spacecraft will remain in stable orbit once the mission is complete. Until then, it will continue to return large quantities of scientific data to Earth. "There are still a number of questions that we would like answered," says Jaumann.

The mission

The Dawn mission is managed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, which is a division of the California Institute of Technology. The University of California, Los Angeles, is responsible for overall Dawn mission science. The Framing Camera system on the spacecraft was developed and built under the leadership of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Göttingen, Germany, in collaboration with the DLR Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin and the Institute of Computer and Communication Network Engineering in Braunschweig. The Framing Camera project is funded by the Max Planck Society, DLR, and NASA/JPL.