Shaped by three natural forces – the landscape north of Eumenides Dorsum on Mars

NASA/JPL (MGS-MOLA) / FU Berlin

- New images from DLR's High-Resolution Stereo Camera on board the Mars Express mission show a region north of Eumenides Dorsum.

- This area is a striking example of how natural forces have shaped our neighbouring planet.

- It is characterised by kilometre-long, streamlined ridges separated by narrow corridors.

- Focus: Space, exploration, Mars

Volcanic activity, asteroid impacts and the raw power of the wind over vast periods of time – the region north of Eumenides Dorsum is a striking example of the interplay of natural forces on Mars. New image data captured by the High-Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) on board ESA's Mars Express mission provide evidence of the dynamic history of this region near the planet's equator. The HRSC is a camera experiment developed by the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) and has been in operation since January 2004.

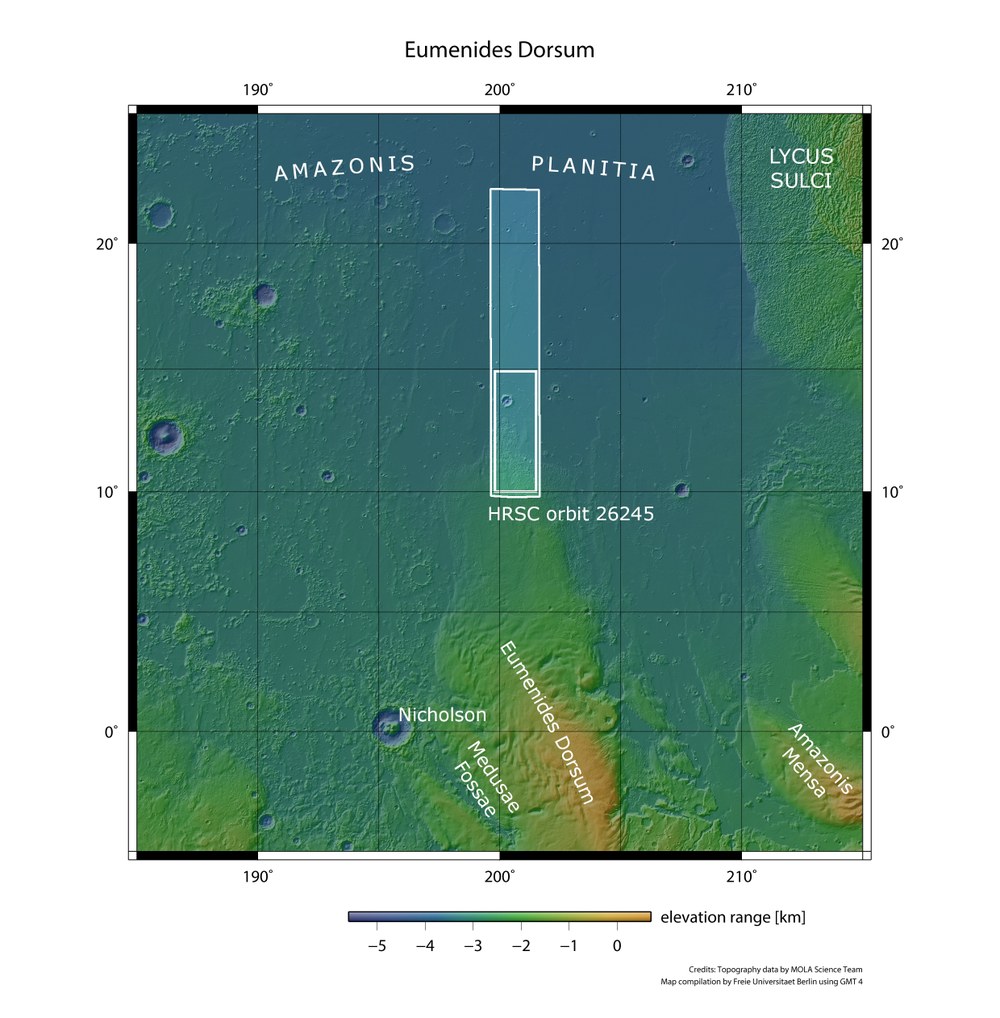

The area shown here is located west of the Tharsis plateau, on the lowland plain of Amazonis Planitia. The image detail shows an area of approximately 28,000 square kilometres – almost as large as Belgium – from different perspectives. Characteristic features include streamlined ridges, some several kilometres long, separated by narrow corridors.

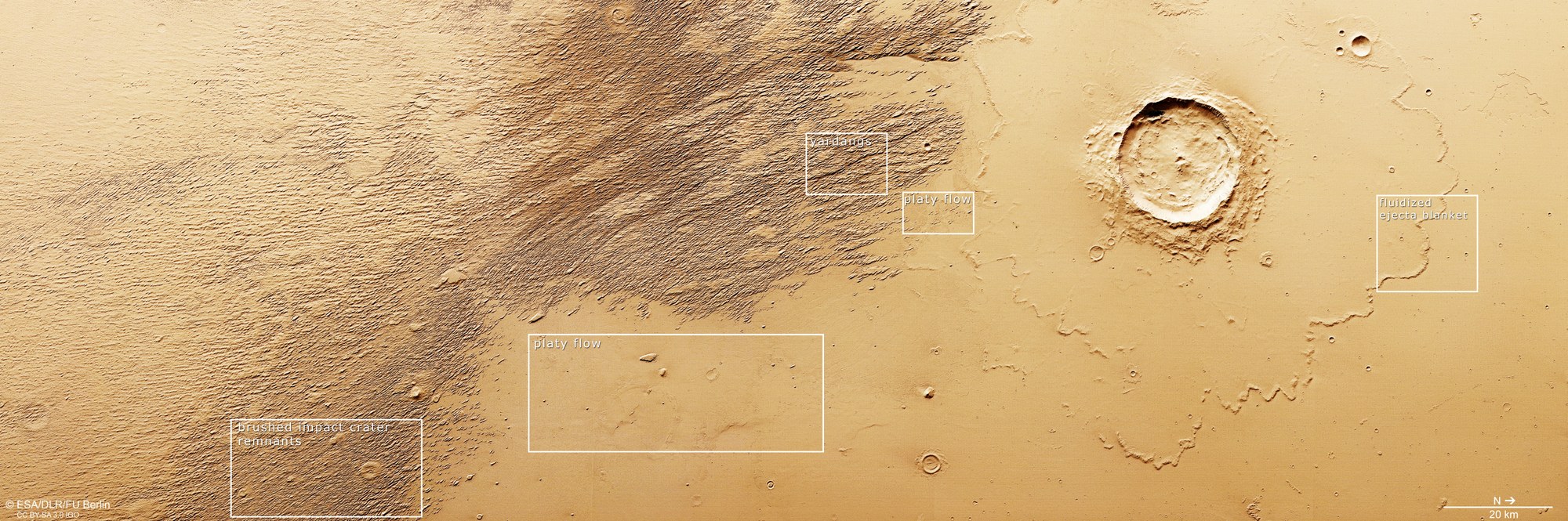

These structures, known as yardangs, are formed by the abrasive force of wind blowing persistently from the same direction. Carrying loose material such as grains of sand, wind acts like a sandblaster, scouring soft sedimentary rock along existing weak zones and gradually removing softer material. Since the wind direction remains constant, the resulting ridges are typically straight. The prevailing wind direction can be inferred from the shape of the yardangs: the broader end always faces into the wind, while the narrower end points downwind. As such, in this area, the wind that shaped the ridges has blown from southeast to northwest.

Impacts, eruptions, wind erosion – what came first?

In the flat area at the eastern end of the region (bottom of the annotated image), structures known as 'platy flows' – which resemble ice sheets, or floes – become visible after a significant increase in image contrast. These features, however, are actually lava flows, presumably from the volcano Olympus Mons, which stands nearby to the east. The surface of these flows cooled and solidified while molten lava continued to move beneath. The persistent movement below caused the solidified crust to fracture, producing characteristic fragments that now resemble plates floating on a sea of lava.

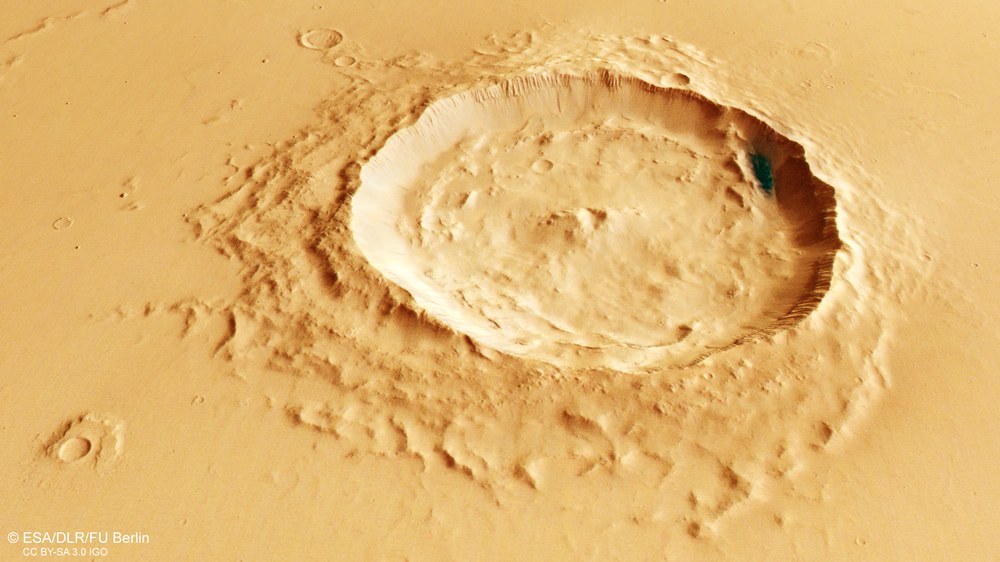

In addition to the large, 'fresh-looking' impact crater with its clearly defined ejecta blanket, smaller and significantly more weathered craters can be seen in the southeast of the landscape. Today, these are recognisable only as rounded elevations amid the yardang field and are referred to as brushed impact crater remnants. They formed earlier than the yardangs, as they have also been heavily eroded by the sandblasting effect of the wind. These crater remnants are likely to have retained their rounded shape because compaction of the ground during the asteroid impact produced more resistant material in specific spots.

The co-occurrence of crater ejecta, lava flows and yardangs south of the large impact crater allows researchers to reconstruct the chronological sequence of the geological processes with considerable accuracy. Since most of the yardangs lie on top of lava flows, they must have formed later. This indicates that volcanic activity occurred here first, followed by an intense reshaping of the landscape by the wind. In all likelihood, the asteroid impact occurred later, leaving behind the large crater. This explains why ejecta covers the lava field and the yardangs terminate to the south of the crater.

As in many regions of Mars, a brief history of geological processes can be reconstructed from a landscape that does not appear particularly remarkable at first glance. However, the reason for the planet's topographical dichotomy – its division into southern highlands lying several kilometres higher than the extensive lowlands north of the equator – remains a mystery in the field of Mars research.

Image processing |

|---|

The image data was acquired by the HRSC (High Resolution Stereo Camera) on 16 October 2024 during Mars Express orbit 26,245. The ground resolution is approximately 20 metres per pixel and the images are centred at approximately 12 degrees north and 200 degrees east. |

|

Related links

The HRSC experiment on Mars Express

The High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) was developed at the German Aerospace Center (DLR) and built in cooperation with industrial partners (Airbus, Lewicki Microelectronic GmbH and Jena-Optronik GmbH). The science team, led by Principal Investigator (PI) Daniela Tirsch from the DLR Institute of Space Research (previously: Planetary Research), consists of 50 co-investigators from 35 institutions and 11 nations. The camera is operated by the DLR Institute of Space Research in Berlin-Adlershof.