Tracking a sea change

Satellites gaze down from hundreds of kilometres above us onto fields, lakes and cities. They provide data for analyses, looking back on past events and forecasting the future. But for Igor Klein, that's only part of the story. "Being there in person, observing changes with your own eyes and talking to people on the ground – that's irreplaceable," says the DLR research scientist. He mostly works at DLR's Earth Observation Center (EOC) in Oberpfaffenhofen, near Munich, unless he's out on a field campaign. Klein is a man who attaches great importance to seeing things with his own eyes.

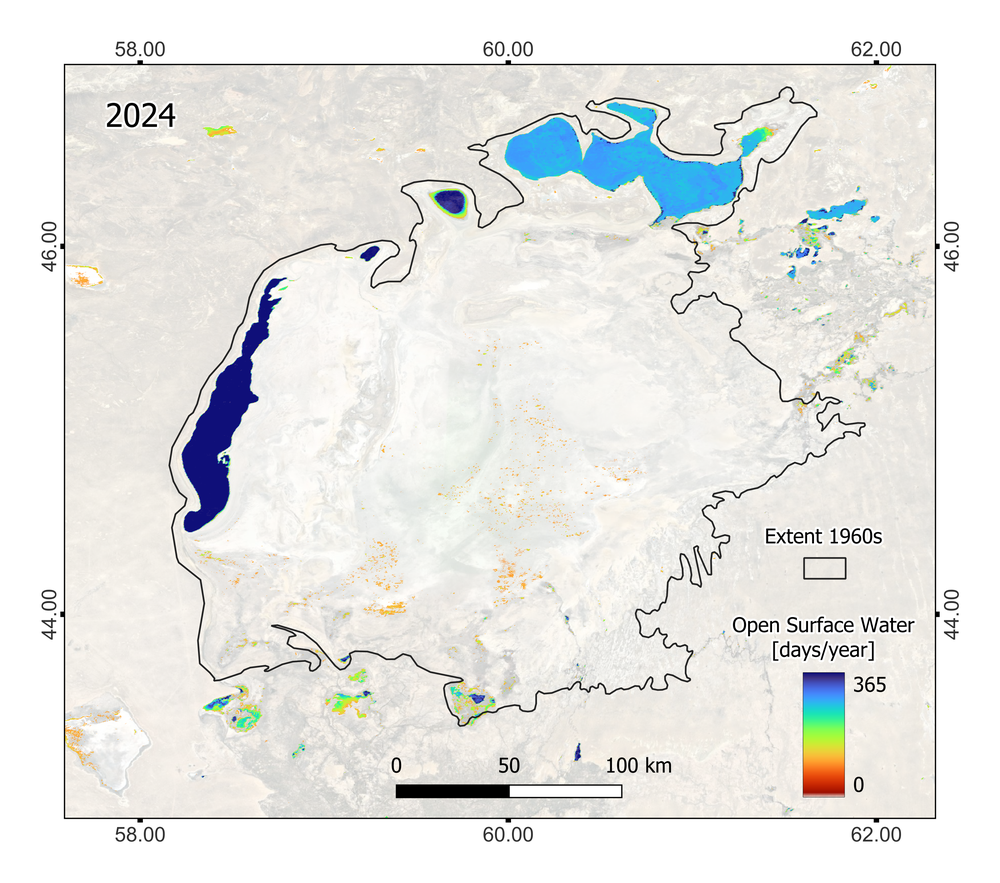

Not too long ago, Klein travelled to the border region between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan – where the Aral Sea could once be found. Together with colleagues, Klein saw the parched ground, rusted ships, desert and sand. Since the 1960s, the Aral Sea – once the world's fourth largest lake – has shrunk down to two small lakes. Year after year, satellite images deliver proof of this retreat. Some hardy plants blossom on the dry, salty ground. There are locusts. "When I saw that, it was like a full-circle moment," he says.

Measuring the biomass

But first things first. Since 2011, Klein has worked with satellite data at DLR to obtain information on changes in land cover and land use. "In my first year, I got the chance to take part in an extraordinary expedition – a four-week field campaign in Kazakhstan. Our objective was to systematically collect plant material to determine the biomass – an essential baseline for verifying satellite results."

Klein also got a sense of the vastness of the surrounding area – the Kazakh Steppe; a dry, grassland plain. He noted the subtle variations in vegetation and transitions in the landscape. "First-hand experience massively helps in interpreting satellite data and the results we derive from it more accurately – not to mention developing a deeper understanding of the relationship between the local regions," says Klein. Indeed, for him, the campaign in Kazakhstan was a pivotal moment: "As a geographer, you bring with you a certain curiosity for different landscapes, ecosystems and cultures. Combining that with this expedition showed me I'd found my dream job. Remote sensing isn't just technology – it's a way to better understand our environment."

Mapping water – and its decline

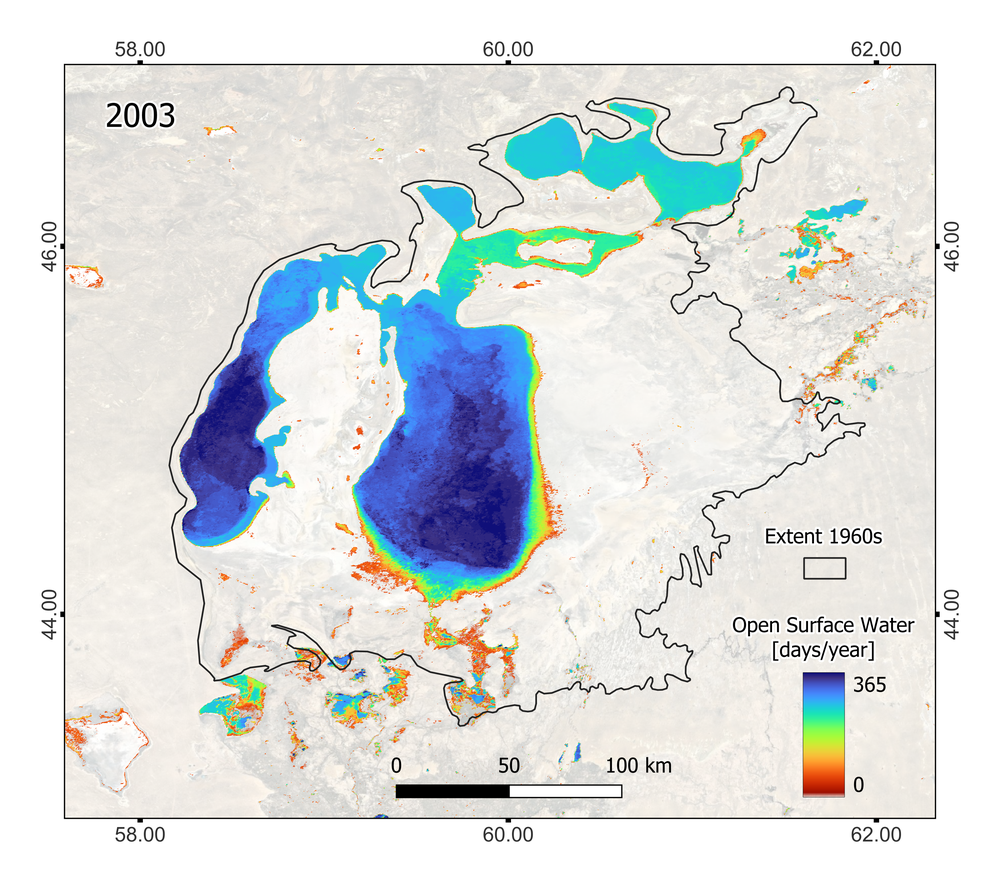

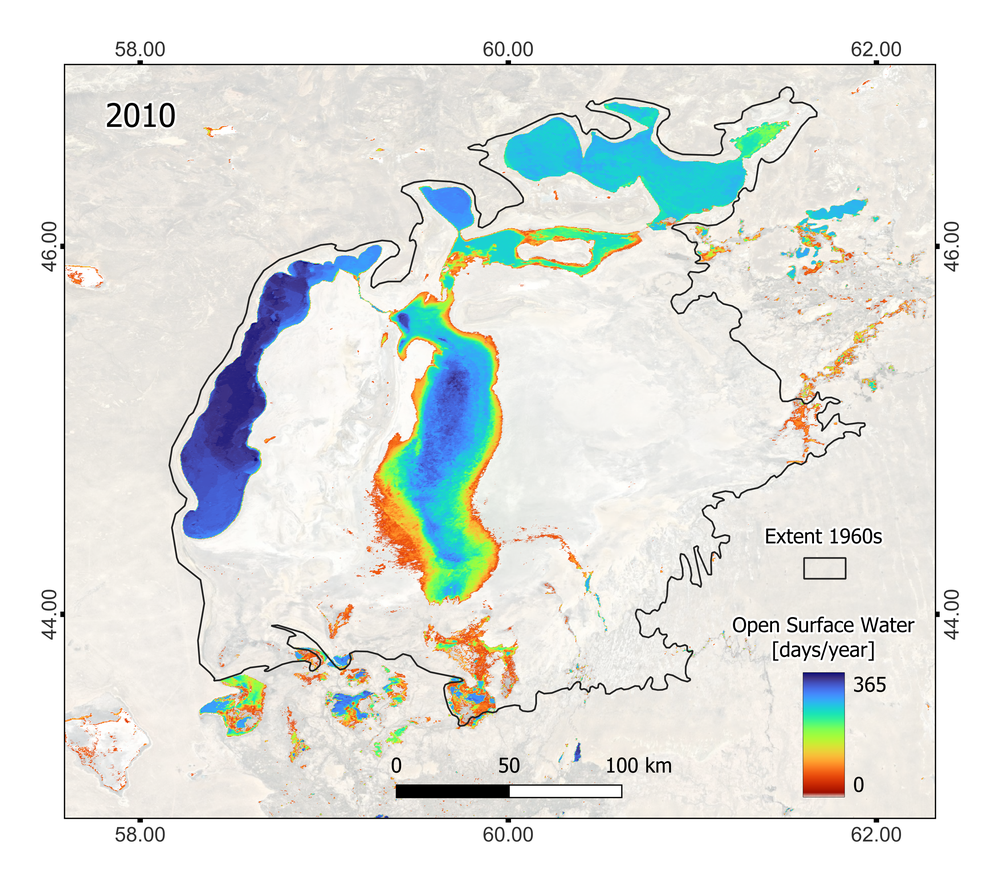

Back to the Aral Sea. DLR’s Global WaterPack (GWP) maps surface waters worldwide with high temporal resolution. The GWP shows how many days per year a given location on Earth was and is covered by water. This makes it possible to identify, for example, exceptional situations and long-term environmental changes – and valuable when it comes to water management. The datasets are publicly accessible via the EOC Geoservice for use by public authorities, industry and research organisations as a basis for their work.

The two lakes that now remain differ greatly from one another. The North Aral Sea in Kazakhstan is stable in terms of its surface area and ecology and freezes over in winter, while the South Aral Sea in Uzbekistan continues to shrink and has a high salt concentration. Klein last found himself in this environment in early summer, as part of a project with Germany's main body for international cooperation (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit; GIZ), focused on the Aral Sea region's long-term ecological and economic development. Earth observation data plays an important role in this, and Klein and his colleagues are asking: Can satellites provide measurement results that encourage the optimal use of land? "We are trying to determine the right parameters for different applications," Klein says. These include, for example, the ratio of soil to vegetation, the spatial and temporal distribution of water and the degree of soil salinity.

To curb soil erosion and minimise dust storms, saxaul shrubs have been planted on the parched ground. "These shrubs are threatened by various pests – one of them being a specific species of locust. This didn't used to be a problem, but this species has now spread," Klein explains, having seen the locust swarms with his own eyes and documented them. This is another focal point of his work, which is underpinned by some 15 years of research at DLR.

Connecting nature and culture

Klein's path to DLR and the realm of Earth observation was not direct – he had originally trained as a carpenter. Studying geography gave him the chance to combine his interests in nature and culture. Remote sensing was a focus that, over the years, became increasingly important. Three years ago, he finished his doctoral thesis on remote sensing in locust management. The aim was to determine the potential of Earth observation to better contain locust outbreaks in different regions of the world, while contributing to food security. Satellite-based locust analyses have already taken him to East Africa, Italy and Australia. "Drought, heavy rainfall or changes in land use influence locust outbreaks all over the world," says Igor Klein.

The German-Kazakh 'Locust-Tec' project ran from 2018 to 2023 and investigated whether and how new technologies can help improve locust management. Klein's project team researched how satellites, drones, digital data acquisition and data administration can help detect locust outbreaks in a timely manner so that the damage can be limited.

“Plagues of locusts are a global problem – they cross national borders and threaten food secu - rity for millions of people. On the other hand, locusts are a protein-rich food source in many cultures,” says Klein. However, established mon - itoring strategies and international networks are in place, and remote sensing data and methods can constitute the key building blocks. That is why DLR’s German Remote Sensing Data Center (DFD) collaborates closely with various stake - holders, including the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization and a range of national ministries and companies. “Only through close cooperation between research, international or - ganisations, local decision-makers and industry can sustainable and effective solutions for locust management be developed,” Klein explains. The results from the project confirm that modern remote sensing methods in combination with artificial intelligence and digital tools have enor - mous potential.

Specialists in earth observation

The German Remote Sensing Data Center (DFD) is a DLR institute with sites in Oberpfaffenhofen and Neustrelitz. DFD and the Remote Sensing Technology Institute (IMF) together form DLR's Earth Observation Center (EOC) – Germany's hub of expertise for Earth observation. Thanks to its ground stations in Germany and beyond, DFD provides direct access to data from national and international Earth observation satellites, processes the data into information products, distributes these products to users and stores all data on a long-term basis in the German Satellite Data Archive (D-SDA). To promote the transfer of knowledge and research, DFD develops subject-specific applications tailored to government agency users.

An article by Katja Lenz from the DLRmagazine 178. Katja Lenz is a press editor at DLR. Growing up in a region shaped by structural change, she finds it fascinating how Earth observation allows us to see, with great clarity and from a huge distance, what is going on below.