Water ice on the Moon – simulated detection in the LUNA facility

- Researchers have used the Polar Explorer campaign to test instruments and robots designed to locate water ice on the Moon.

- When humans return to the Moon, they will need resources; water ice can also be used to produce rocket fuel and drinking water.

- Testing was carried out under realistic conditions across 700 square metres of LUNA Moon dust.

- Focus: Space, Moon, robotics, exploration, planetary research

It is very likely that there is water ice on the Moon, for example in its south pole region where some craters never see sunlight. Water ice may have been hidden in these 'cold traps' for billions of years, but can humans use this water when they return to the Moon? Is the water frozen solid in the lunar dust? Is it chemically bound? Or are there perhaps even layers of ice in the permanently shadowed craters, either on the surface or underground? To address these and other unanswered questions, the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) has teamed up with several universities to test how water could be detected on the Moon. Tests took place at the DLR–ESA LUNA Analog Facility in Cologne, where robotic and crewed lunar missions can be prepared in a realistic environment.

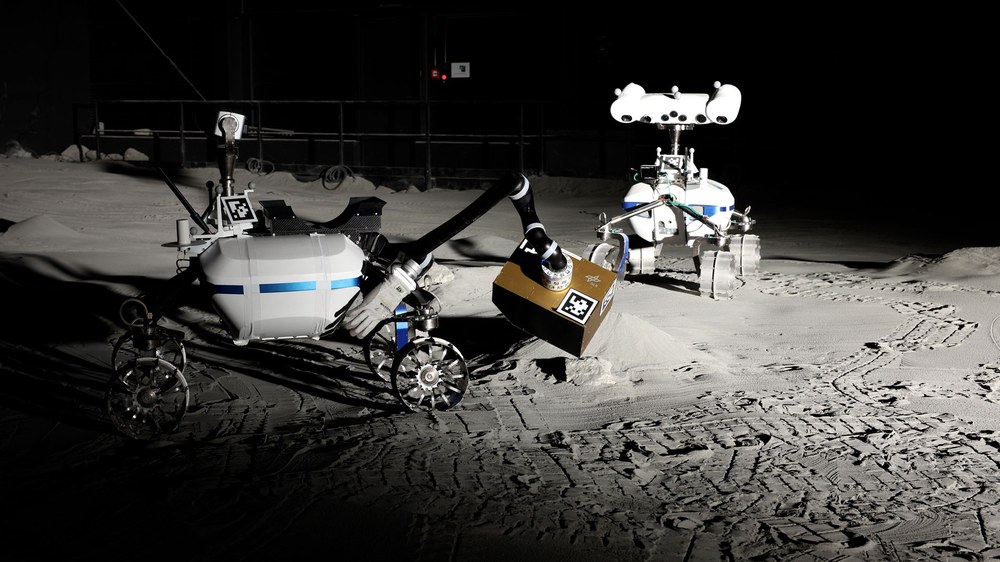

LUNA offers researchers a 700 square metre area filled with simulated lunar dust. The material is remarkably similar to the regolith on the Moon and is therefore ideal for testing instruments and robots. "If we want to find and map water ice on the Moon, we need to be very mobile on the surface. That's why we used two rovers equipped with special instruments. The combination of different methods offers advantages and proved to be particularly reliable here," explains Nicole Schmitz, a planetary scientist from the DLR Institute of Space Research. She led the Polar Explorer campaign alongside the LUNA team. Initial results are already available – the researchers were successful, locating and mapping simulated water ice in the LUNA facility. The data obtained is now being evaluated in detail.

How do you find water ice in a lunar simulation?

The floor area in the LUNA facility is three metres deep and completely filled with regolith. Concealed within are not only a mock lava cave but also numerous acrylic objects. To the radar instruments used, these appear as pure water ice hidden beneath the surface – the contrast between pure ice and Moon regolith is very similar to that between acrylic and LUNA regolith – which is precisely what the radar detects. For the Polar Explorer campaign, a seismic source (PASS – Portable Active Seismic Source) generated additional measurable vibrations and helped reveal the simulated water ice in the ground. To achieve this, fibre-optic cables were laid out in advance – cables that could equally be deployed on the Moon. The configuration formed a geophysical network for distributed acoustic sensing, a technique whereby tiny deformations in the fibre-optic cable indicate movements in the ground that provide clues about subsurface structure.

Water has also been detected in lunar rock, where it can be trapped within the crystal structure of mineral grains or in volcanic glass, for example. To detect hydrogen in rock samples, the researchers used a technique known as LIBS (Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy). LIBS uses a pulsed laser to generate a small plasma cloud from the sample material. The light emitted by the plasma provides information about the elemental composition of the material. The LIBS instrument is housed in a payload box, with a robotic arm holding it directly against the target. The robotic arm, in turn, is part of LRU2 (Lightweight Rover Unit 2), a vehicle from the DLR Institute of Robotics and Mechatronics.

LRU2 is equipped not only to hold laser boxes but also to collect samples, perform tasks autonomously and carry out calculations. It forms a rover team with LRU1, which maps the lunar surface with a multispectral stereo panoramic camera, easily recognisable on the rover's wide head. Such cameras see much more than just colours, as they measure image data across wavelength ranges that far exceed what the human eye can perceive. On the Moon, this would allow information about the mineralogical composition of the surface to be recorded, mapped and quantified. An added benefit is that the rover can use the resulting terrain model to find the safest route to its destination.

For the Polar Explorer campaign, LRU1 pulled a trailer carrying ground-penetrating radar equipment and scanned the subsurface. Combined with data from the camera, the researchers obtained a three-dimensional representation of the area under investigation – both surface and subsurface. In an actual lunar mission, the instruments would not be mounted on a trailer but permanently installed inside the rover.

Successful dress rehearsal for a complete mission

The Polar Explorer campaign is based on a mission concept that DLR researchers have proposed to the European Space Agency (ESA). The concept could be selected for a lunar mission using the Argonaut lander, a spacecraft currently under development that is designed to provide infrastructure, instruments and resources. "As part of this mission concept, we have now brought all the elements together for the first time. The teams with the rovers and instruments have tested the entire operational sequence and have shown that all the elements are ready and working," adds Schmitz. A model of the Argonaut lander is on display at LUNA.

From Mount Etna to the LUNA hall

LRU1 and LRU2 are familiar with rough terrain – they have already proven themselves in training missions on Mount Etna in Italy. As part of the ARCHES mission, LRU1 and LRU2 explored the area and collected samples, working alongside other robots. "In the LUNA hall, the rovers have navigated autonomously, avoided obstacles and selected and used the appropriate instruments. All of our goals in the Polar Explorer campaign were achieved," says Martin Görner from the DLR Institute of Robotics and Mechatronics. The rovers also coped well with the difficult lighting conditions, simulating the polar regions of the Moon, where the Sun is always low on the horizon and dazzles the camera systems. A Sun simulator in the LUNA hall recreates this effect.

How did water actually get to the Moon?

"Scientists used to agree that the Moon was bone dry," explains Schmitz. "Now we have lots of evidence that there is water ice on the Moon – and at the same time lots of unanswered questions. It's extremely exciting." The ice could have arrived with impacts from comets or icy micrometeorites. Alternatively, it could have originated from an interaction between solar wind and lunar dust, or it may even be a remnant of early lunar volcanism. "If we solve this mystery, we will also learn more about the evolutionary history of the Solar System," says Schmitz.

Water ice is essential for exploration. If humans are to work and live on the Moon, they will need access to resources. Drinking water is one important requirement, and if the water is split into hydrogen and oxygen, it could also be used to produce rocket fuel.

Related links

- The LUNA Moon facility

- DLR Institute of Space Research

- DLR Institute of Robotics and Mechatronics

- Microgravity User Support Center Department (MUSC)

- Luna Analog Facility website

- DLR project – Robotics mission ARCHES

- DLRmagazine article – League of extraordinary robots

- DLR news – The flying observatory SOFIA discovers water molecules on the Moon

The LUNA Analog Facility

The LUNA Analog Facility in Cologne is a unique centre for preparing future crewed and robotic lunar missions. The LUNA hall houses, among other things, a 700 square metre simulated lunar surface. It is filled with a simulated Moon dust that closely resembles real regolith. Stones and rocks are modelled on lunar geology, and permanently installed seismic sensors provide reference data for experiments. A Sun simulator recreates lighting conditions like those on the Moon. An area lowered by three metres allows for testing of drilling techniques and radar measurements. In future, experiments with an inclined plane will be carried out on an adjustable ramp.

The Gravity Offloading System will soon replicate the gravity of the Moon. This system of trolleys and ropes will be installed on the ceiling, so that astronauts or rovers can move around as if they were on the Moon with one-sixth of their Earth weight. FLEXhab is a living area for astronaut missions. The EDEN LUNA research greenhouse will be connected as an additional external module. The LUNA Analog Facility was officially opened in September 2024. The state of North Rhine-Westphalia is supporting the joint project between DLR and ESA with 25 million euros of funding.

Participants in the Polar Explorer campaign

Alongside the DLR Institute of Space Research, the DLR Institute of Robotics and Mechatronics and the LUNA team from DLR's Microgravity User Support Center, several other universities and institutions played an important role in the Polar Explorer campaign. The ground-penetrating radar (GPR) attached to LRU1 comes from the Technical University Dresden (TUD). GPR provides centimetre-level resolution. The TUD team tested several prototypes and sensor combinations in the LUNA facility. Teams from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) and the University of Cologne focused on distributed acoustic sensing, contributing to the detection of water ice – in this case pieces of acrylic – beneath the surface. A team from the University of Tokyo supplied the two 'seismic sources'.