Big future for small satellites

Some are no bigger than a matchbox, yet the future of space technology belongs to them: small satellites. The smallest, the cube-shaped PocketQube, measures just five centimetres along each edge. The real stars of the family, however, are undoubtedly the CubeSats. With dimensions of ten by ten by ten centimetres, they can be used for a wide variety of space applications, produced inexpensively on an industrial scale and combined into modular systems of almost any size. Beyond their shape, small satellites are classified by weight into categories such as pico, nano, micro and mini. But as much as the members of this family differ in size, weight and function, they all have one thing in common – they weigh no more than 500 kilograms.

More than 9000 small satellites launched to space

"Small satellites are incredibly versatile," says Andres Bolte, responsible for small satellites at the German Space Agency at DLR. "They are already being used in almost all classical areas of spaceflight – observing Earth, exploring space and enabling communications and internet access even in remote regions of the world."

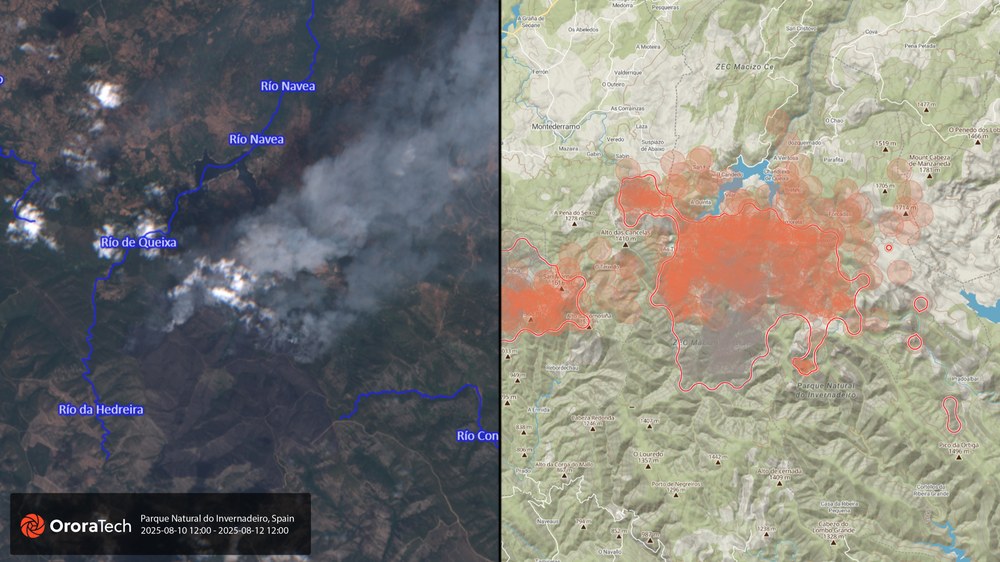

OroraTech

Current figures clearly demonstrate the high demand for these small satellites, with more than 9000 launched into orbit between 2015 and 2024. These include individual research satellites, small formations and commercial satellite constellations. "The benefits of small satellites are obvious," continues Bolte. "They are inexpensive, flexible and, in formation, can cover large areas of Earth's surface with high acquisition rates."

Monitoring wildfires and detecting ocean waves in 3D

Many more small satellite systems are currently in the planning or are already being built or expanded. They are used, for example, for wildfire detection. Here, the advantage over their larger siblings – such as the Sentinel satellites from the European Union's Copernicus Earth observation programme – is clear. While the Sentinels can only fly over and observe a specific region once a day, the OroraTech system, with its fleet of small satellites, will be able to perform five flyovers every day once completed. This high repetition rate provides a far more up-to-date picture of forest fire events. DLR has licensed its own AI-based method for detecting and measuring burned areas – a technology that will be integrated into OroraTech's commercial Wildfire Solution platform.

Another example is ocean observation. Formations of small radar satellites can be used here to detect ocean waves and record them in 3D – improving the safety of international shipping.

Europe's answer to Starlink?

In the future, small satellites are also expected to increasingly take on security-related tasks in the civilian and military sectors – helping to verify compliance with political initiatives such as the EU Supply Chain Act or the Paris Climate Accords. The best-known network of small satellites orbiting Earth is the early Starlink fleet operated by US company SpaceX. In addition to civilian use, Starlink also supports intelligence gathering in war and crisis-hit regions. "Without small satellites, the Ukrainian military's ability to communicate would be severely limited," says Bolte.

OroraTech

The risk of such dependence on partners – especially on individual companies – is now acknowledged in Europe, against a backdrop of increasing political instability worldwide. "It is vital to ensure Europe's autonomy in defence and reconnaissance from space," stresses Walther Pelzer, Member of the DLR Executive Board and Director General of the German Space Agency at DLR. "Swarms of small satellites provide an excellent solution".

Plans are now underway to massively expand the constellation from French satellite operator Eutelsat to achieve greater technological independence. But the road to European autonomy is long: Eutelsat's fleet of approximately 650 satellites in low Earth orbit is a fraction of the size of the 7000-strong Starlink system – and US satellites are also more technologically advanced.

Allies fight against cyberattacks on energy grids

Extensive networks with large numbers of satellites will be essential for future space applications – from ensuring national energy security and monitoring supply chains to supporting widespread autonomous driving. Dense networks of small satellites could, for example, become allies in defending against cyberattacks on national energy infrastructure, where attackers aim to trigger widespread blackouts that paralyse industry, the economy and transport.

Germany's energy infrastructure is secured by 'redundant networks' – where a backup system automatically kicks in if one system fails. But what happens if this is also attacked and shut down? In the future, CubeSat networks could take over and ensure communication between facilities – from gas-fired power stations and wind turbines to balcony solar systems. The mini satellites would not only be able to switch systems on and off, but also increase their security through updates.

CAPTN-1 – testing new space technologies 'on site'

DLR has recently launched the CAPTn programme (CubeSat to Accommodate Payloads and Technology Experiments), in which new space technologies can be tested on CubeSats directly 'on site' – in other words, in space. For this, they must withstand both the vibrational stresses of launch and the environmental conditions in space – extreme heat and cold, radiation and being in a vacuum. The first satellite in the planned series, CAPTn-1, is expected to launch in summer 2026 on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. It will orbit Earth for approximately two years.

The benefits of small satellites are obvious. They're inexpensive to build and can be deployed flexibly.

The small satellite has a volume of 12U, with one unit (1U) corresponding to the ten-by-ten-by-ten centimetre cube described earlier. The satellite is being manufactured by the French space company U-Space, which is also integrating the payloads. "Four special DLR innovations will be tested on CAPTn-1," explainsFereydun Kaikhosrowi from DLR's space research programme. "The ScOSA, DLReps, Smart-Retro and GSDR technology experiments will all be on board at launch."

ScOSA (Scalable On-Board Computing for Space Avionics) is a new type of computer developed by DLR for use on space missions. The project combines space-proven processors with commercially available processors that are cheaper and more powerful, but less robust. To ensure the system remains reliable even if processors fail, the ScOSA computer system consists of various decentralised computing nodes. Special software then detects faulty nodes and redistributes their tasks to others. Where possible, damaged processors are repaired and, depending on their restored performance, reintegrated into the system.

DLR is developing wood-based materials for satellite structures. This should make combustion during re-entry as low-emission as possible.

DLReps is an experiment that focuses on intelligent batteries for use on space missions. In this sytem, a dedicated software handles battery management, collecting data on the system's condition and making autonomous decisions. Novel algorithms are used to determine the state of charge and health, as well as detecting faults in the battery cells. The software monitors and controls the thermal system and ensures that the voltage of the battery cells remain balanced, keeping the overall system in good working order.

Like a 'number plate' for satellites, the Smart-Retro experiment equips a retroreflector – three mirrors that reflect incoming light back to its source regardless of the angle of incidence – with a polarisation optic. This reflected light can then be tracked from the ground using lasers as an individual signal. As well as identifying satellites, Smart-Retro enables millimetre-precise position determination, calculated from the time the laser pulse takes to travel from the ground to the reflector.

U-Space

The GSDR (Generic Software Defined Radio) platform will be used to receive high-frequency aircraft signals during the CAPTn-1 mission. What makes it special is its high bandwidth, which allows it to process multiple frequencies coming from different directions simultaneously and independently. This enables better analysis of issues that affect simple receiver systems, such as signal collisions, and improves reception performance from orbit.

What goes up, must come down

The sharp rise in the number of small satellites also brings new challenges. Over the coming years, thousands will reach the end of their typically short lives and burn up in Earth's atmosphere. To ensure this happens in the most environmentally compatible way, DLR has launched the TEMIS-DEBRIS and Bio Strux projects. In TEMIS-DEBRIS (Technologies for the Mitigation of Space Debris), researchers are primarily concerned with designing a satellite that breaks down into the smallest possible combustible parts upon re-entry. While satellites in higher orbits are usually parked in 'graveyard orbits', low-flying satellites are allowed to burn up as they re-enter Earth's atmosphere. The more completely the orbiter's individual components burn up, the lower the risk that debris will reach the ground and cause damage. Certain components are therefore designed to detach under aerodynamic and thermal loads or via 'predetermined breaking points' as they enter the atmosphere. The development of combustible materials is also a key focus of the project.

But even when a small satellite burns up, it still affects the environment – especially in the very sensitive upper layers of our atmosphere. For example, the combustion of chemical propellants or batteries produces vapours that could affect the climate. The Bio Strux project is dedicated to addressing this problem: "DLR is developing wood-based materials for satellite structures," continues Kaikhosrowi. "This will make combustion as low-emission as possible." Wood, a natural material, also has the advantage of withstanding high loads, temperature fluctuations and vacuum conditions.

"In the long run, small satellites will never fully replace their larger counterparts like the Sentinels," says Anke Pagels-Kerp, DLR Divisional Board Member for Space. "Complex scientific instruments require a lot of space and extremely powerful energy supplies. Rather, small satellites are a perfect complement and open up many new technological possibilities in space."

An article by Diana Velden from the DLRmagazine 178. Diana Velden is an editor in DLR Communications with many years of experience in public relations.