Dreaming of the circle

adobestock.com – FiledIMAGE

When I watch my eight-year-old son play, I am often moved. A few building blocks are all it takes, and he's away. He hums happily as he puts them together, then tears them apart with frustrated growls. He starts off with a blank slate; the ideas come as he builds. Some things simply won't work, while others succeed on the first try. If he can't construct something with the bricks at hand, his imagination takes care of the rest. Of course, one of the things my son builds is aeroplanes. He assumes I have a certain expertise. Is the tail long enough? I purse my lips. Almost. Fine then, another brick is added. Finally, I have to approve the plane. Does it look real? I smile and shower my son with sincere praise.

But then, he's already pulling off the engines, keen to get started on another bright idea. "Wait a second!" I say, "If you want to build a real plane, you can’t just take it apart when you’re done! You have to put it on a shelf and buy new bricks!"

A circular economy in Aviation

My pleas fall on deaf ears. But I have inadvertently described how the aviation industry currently deals with aircraft that have reached the end of their service life. Once expensive components like the engines have been removed, the remainder often ends up in special graveyards where hundreds of aircraft slowly rust away. Yet the European Green Deal calls for climate-neutral aviation by 2050. Not only that – the sector is supposed to be fully circular by then, meaning completely embedded in a functioning circular economy. Wouldn’t that begin with comprehensive recycling?

Bild: stock.adobe.com – aapsky; Grafik: raufeld

Someone who should know is researcher Ligeia Paletti from the DLR Institute of Maintenance, Repair and Overhaul (MRO). The circular economy, she stresses, is by no means just about recycling. This misconception stems partly from its many different, often conflicting, definitions. Paletti believes that all parties need to agree on a solid conceptual framework – and this is where her research comes in. "Everyone agrees that sustainable aviation must follow the principles of the circular economy," she says. "But for aviation to become truly circular, you have to see it as a complete system designed to preserve the value of all components as much as possible. It's not enough to make a single piece of the puzzle circular. Imagine making a recyclable plastic bottle that no shop will take back – you’d gain nothing by doing that."

Repair and maintenance

Some circular principles have long been applied in the MRO sector. "Repairs have always been an integral part of aviation," says Paletti. "This sets the industry apart from others where products have not been primarily designed with repairability in mind. But repairability has always informed aircraft design."

Video: Ligeia Paletti on the circular economy in aviation

Your consent to the storage of data ('cookies') is required for the playback of this video on Quickchannel.com. You can view and change your current data storage settings at any time under privacy.

Admittedly, maintenance was not originally considered critical in aviation for reasons of sustainability. It was – and still is – primarily geared towards the profitable and safe operation of very expensive, complex products. As such, some stakeholders are surprised to learn that decades-old practices are already considered circular.

But maintenance is ultimately just one building block in circular aviation. If two materials are to be joined together, consideration must be given to how they can be separated again at some point in the future. And aircraft operations must also be considered afresh. Ultimately, this affects all processes in and around the aircraft and at the airport – nothing less than the entire air traffic system.

Supply chains in uncertain times

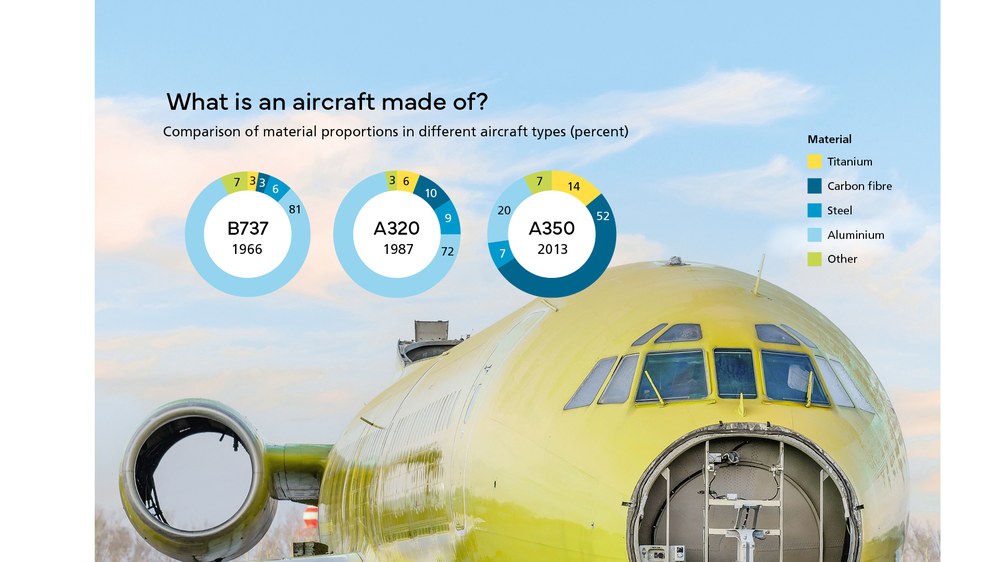

Sustainability is not the only concern driving the transformation to circular aviation. Robust and resilient supply chains are just as important. Few materials illustrate this as clearly as titanium. First used in aircraft such as the Boeing 707 as early as the 1950s, the proportion of titanium in aircraft has steadily increased. There are a number of reasons for this: titanium is lightweight and extremely strong; it can withstand large temperature fluctuations, such as those inside an engine, and it is compatible with many composite materials. The result: titanium saves space and weight – which is why present-day commercial aircraft such as the Airbus A320neo and Boeing 737 MAX are made of approximately 12 percent titanium. Titanium is no longer limited to particularly critical components such as engines and wings, but is also found in the landing gear and fuselage – a trend driven by the simple fact that a lighter aircraft consumes less fuel, emits fewer greenhouse gases and is cheaper to operate.

Before its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russia was the main titanium supplier for both European and American aircraft manufacturers and suppliers. Since then, other countries have filled the gap – a huge challenge when you consider that air passenger traffic is expected to grow by 4.5 percent per year. Several thousand new aircraft have been ordered and will enter service in the coming years – with an increasing titanium content. It is not hard to see that Europe could become seriously dependent on other markets unless smart solutions to the material shortage are found.

DLR researcher Tim Hoff has scrutinised in detail the current and future Titanium requirements by analysing data from more than 55,000 aircraft, both active and retired. "Worldwide, approximately 13,600 tonnes of titanium are sitting in decommissioned aircraft," says Hoff. What could be more logical than recycling the titanium lying around? "It’s certainly an enticing prospect," says Hoff. "Technically, the hurdles for recycling titanium are low. The problem is primarily economic." The titanium is widely distributed across many aircraft components, so there is not a large enough economic incentive to painstakingly extract and collect it. Added to this are the regulatory restrictions. "The quality requirements for titanium in aviation are very high," explains Hoff. "At present, it is very difficult for recycled material to meet these standards. But it can certainly be used in other industries."

A longer life

Recycling alone, then, cannot solve the challenge. Instead, Hoff is researching a different approach. He has demonstrated that extending the service life of aircraft is a much better strategy. Even if decommissioned aircraft are fully recycled, they are, on average, only in service for 25 years.

It is better to reduce demand – and this can be achieved by simply flying aircraft longer. "Extending the average lifespan by just two and a half years would save almost ten percent of material," Hoff explains. "This is three times as much as by recycling alone. If you combine recycling with extending the service life, savings of up to 15 percent are possible."

The fact that it is possible to use aircraft for longer than planned is thanks to their excellent maintainability. Aircraft are regularly maintained right up until they are decommissioned, and some components are replaced several times – practically everything is replaceable. In principle, an aircraft’s service life can be extended almost indefinitely. Ultimately, however, several strategies must be combined to meet future material needs and ensure stable supply chains: "Operational processes and MRO present particularly large potential for circular aviation," Hoff emphasises.

Interview on titanium deficiency and possible solutions

Your consent to the storage of data ('cookies') is required for the playback of this video on Quickchannel.com. You can view and change your current data storage settings at any time under privacy.

The future of maintenance

What springs to mind when you hear 'aircraft maintenance'? Perhaps highly efficient processes that have been honed and perfected over decades. There is, in fact, still room for improvement in maintenance, as Robert Meissner at the DLR Institute of Maintenance, Repair and Overhaul, explains: "Tyre pressure checks are carried out at strictly defined intervals," he says, citing a familiar example." The same applies to many other maintenance tasks. But in 90 percent of these preventive measures, nothing actually needs changing." Intuitively, we might assume that this multitude of measures is primarily due to the high safety standards in aviation. But, there is another crucial reason. "Scheduled measures can be integrated into a flight plan. If, however, an unplanned measure such as a tyre change becomes necessary, this can ground an aircraft for an indefinite period."

Meissner and his colleagues are therefore researching new maintenance strategies with that in mind. The goal is to move away from rigid schedules and towards ondition-based inspections – ideally, just before maintenance is actually required. However, this requires precise knowledge of the condition of the components. "Newer aircraft models already capture a wealth of data," says Meissner. "Ideally, we should be using this data for maintenance by creating the most accurate predictions we possibly can about when a component will fail."

New maintenance strategies

Meissner believes that this forecasting methodology, known as predictive maintenance, is only the starting point for an even broader approach. To put this concept into practice, it is necessary to know not only when a component will fail on a particular aircraft, but also at which airport it will be located, whether spare parts are available nearby and whether an MRO provider is on hand to install them. "This far-reaching strategy, known as prescriptive maintenance, takes the entire aviation system into account," says Meissner. "It can significantly optimise maintenance processes and avoid unnecessary steps." Prescriptive maintenance could therefore play a key role in aviation’s path towards circularity.

"If we want to achieve our sustainability goals," adds Ligeia Paletti, "we must broaden our perspective and look beyond the flight phase and carbon dioxide emissions, and also take into account the significant impact of MRO and end-of-life processes." Last year, the EU's 'right to repair' directive entered into force, requiring all industries to make their products repairable, even beyond the warranty period. "In this respect," says Paletti, "aviation is already ahead of most other everyday consumer goods."

By now my son has taken his toy plane apart again. Well, not entirely. The wings turned out well so he’s keeping them, for now, but he’s not satisfied with the rest. Perhaps it’s no surprise to learn that even with building blocks, it’s hard to build a perfect circle. Still, that shouldn’t stop us from trying.

An article by Phillip Czogalla from DLRmagazin 178. Phillip Czogalla is responsible for communications at the DLR Institute of Maintenance, Repair and Overhaul. He is fascinated by the complexities of aircraft maintenance and knows how crucial it is in bringing about more sustainable aviation.