On the trail of flight

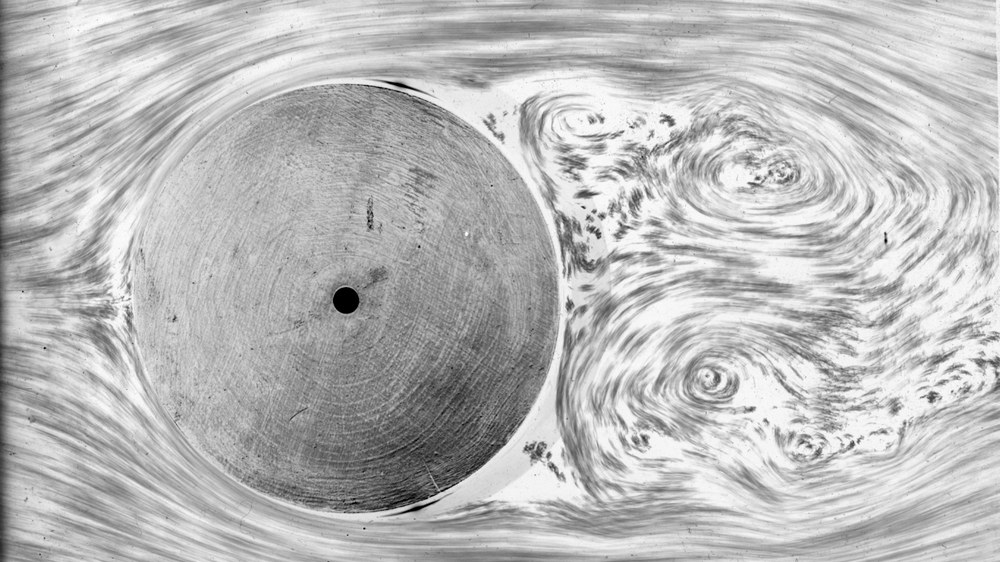

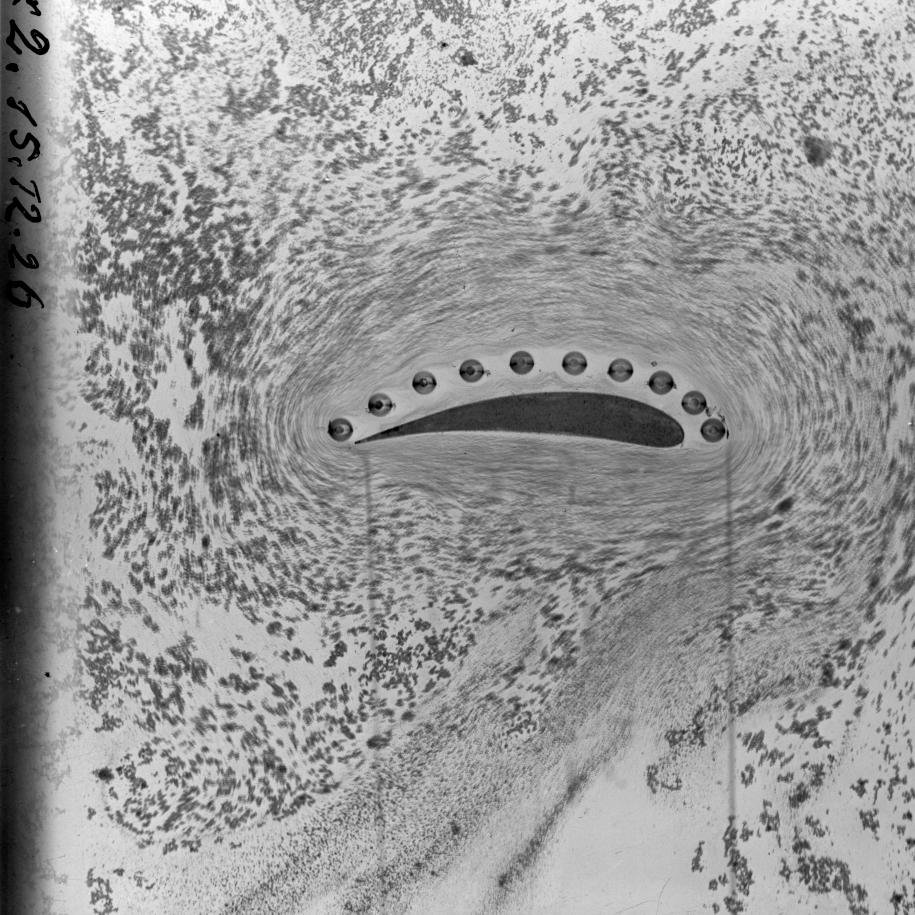

He was one of the first in Germany to systematically study aerodynamics and hydrodynamics. Using experimental apparatus he built himself, zoologist and physicist Friedrich Ahlborn succeeded in visualising flows in water and documenting them on glass plate negatives. In doing so, he created an important foundation on which other flow researchers could build – including Ludwig Prandtl (1875–1953), director of the first predecessor organisation of DLR in Göttingen.

From Göttingen to Quakenbrück and back

Friedrich Ahlborn was born on 4 January 1858 in Göttingen, Germany, where he attended the royal secondary school (Königliches Gymnasium). At the age of 15, he left school and worked for a land surveying group that produced maps of Göttingen and its surroundings.

In 1878 he completed his pre-university studies in Quakenbrück. Ahlborn then returned to Göttingen to study zoology, geology, chemistry and mathematics at the university there. He went on to earn his doctorate under the supervision of Göttingen zoologist Ernst Ehlers (1835–1925), writing his dissertation on the pineal gland of lampreys.

The path to flow research

In 1884 Alhborn joined the faculty of a secondary school in Hamburg, where he was tasked with overhauling its science curriculum. Together with colleagues, he cultivated a collection of geological, mineralogical and zoological specimens and established a chemistry laboratory where students could carry out their own experiments. Alongside his teaching, he began researching the flight behaviour of flying fish and plant seeds. He was particularly fascinated by the seeds of Zanonia, a gourd plant native to the South Seas. Zanonia seeds are not only carried long distances by the wind but are characterised by their remarkably stable flight position.

Pioneering work in the living room

To get to the bottom of the phenomenon of flight, Ahlborn constructed his first test facility in his living room. It consisted of a small standard aquarium, a ruler, a wooden clip and an index card. He filled the aquarium with water and added eosin, a red dye. He then attached the index card to the centre of the ruler using the wooden clip and immersed half the card in the water. Slowly, he moved the ruler along the edge of the tank, dragging the card through the water. With this setup he was able to observe changes in pressure on the card at different speeds. His homemade setup was not, however, adequate for a full analysis of flow processes.

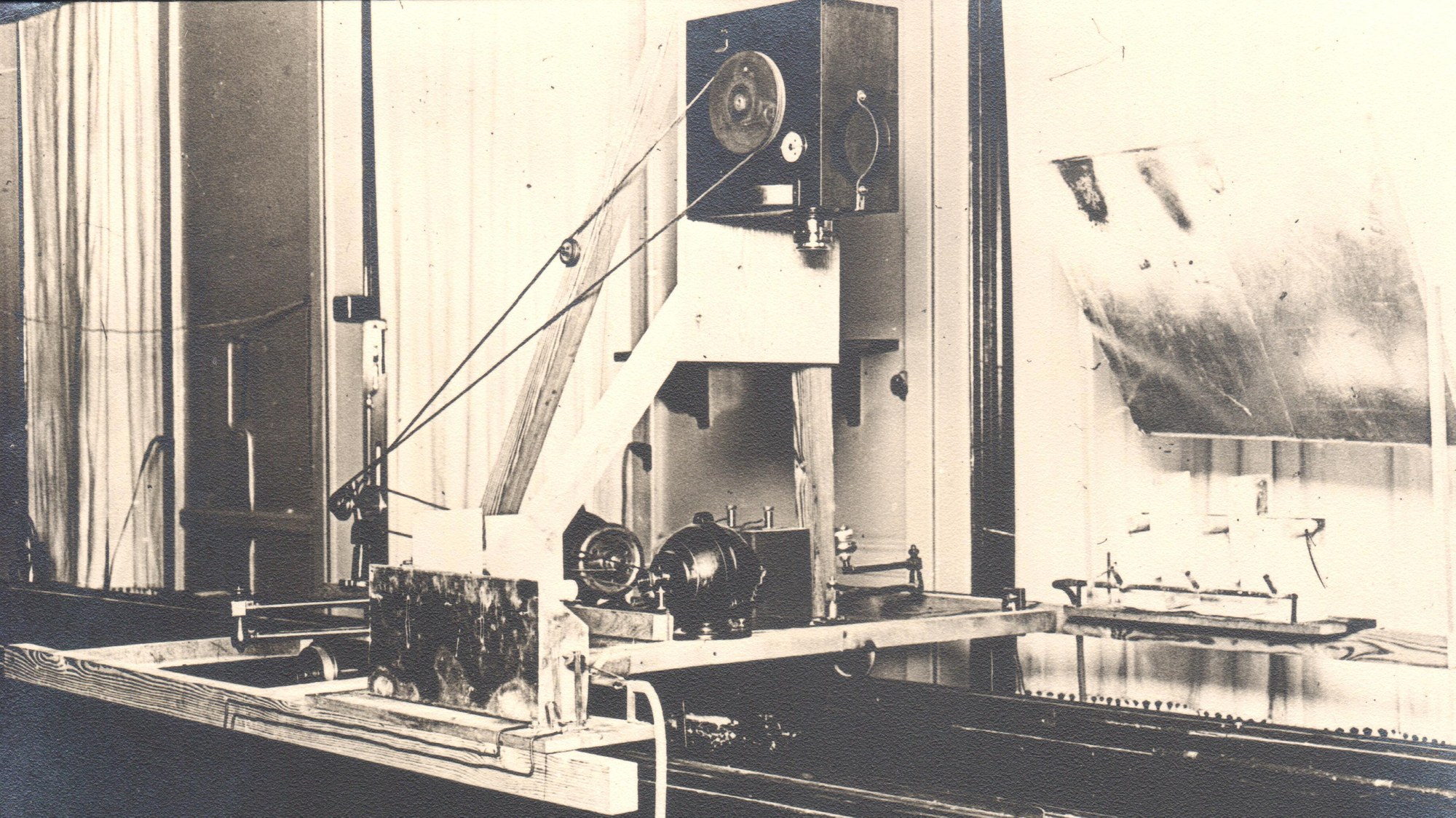

Together with his student Max Wagner, he designed a towing tank ten metres long and one metre wide. They fitted a towing device above the water channel, allowing them to pull various model bodies through the water while also carrying a camera to photograph the flows.

During the First World War, Ahlborn's work was deemed crucial for the war effort. He was allocated his own institute at the aircraft maintenance facility in Berlin-Adlershof, where he built a 20-metre towing tank. There, he and his colleagues not only studied ship models but also propellers and airship models, aiming to improve their aerodynamic design. After the war, aeronautical research was banned in Germany, leading to the dismantling of Ahlborn's test facility. The water channel was taken over by the University of Aachen, where Theodore von Kármán (1881–1963) was head of an institute dealing with aerodynamics, where it was mothballed and gradually disassembled over time.

'Old glass' from Canada

Ahlborn, who after the war returned to operating a small towing tank in his home in Hamburg, died in 1937. Part of his estate was donated to the Deutsches Museum in Munich shortly after his death. In early 2025, Ahlborn's great-granddaughter, Dorit Mason, contacted DLR.

Her father, Boye Ahlborn, who lives in Canada, has numerous documents and dozens of glass plate negatives which belonged to his grandfather. An initial tranche of glass plate negatives were handed over in London in early 2025. The 'old glass' from Canada is currently in DLR's Central Archive, but is expected to make its final home in the Deutsches Museum archive in Munich, where it will complement the existing Ahlborn collection.

An article by Jessica Wichner from the DLRmagazine 178. Jessika Wichner heads the DLR Central Archive and personally received the first batch of glass plate negatives from Ahlborn's great-granddaughter, when the two met during a stopover in London while travelling.