HALO-South hunts trace gases in clean air

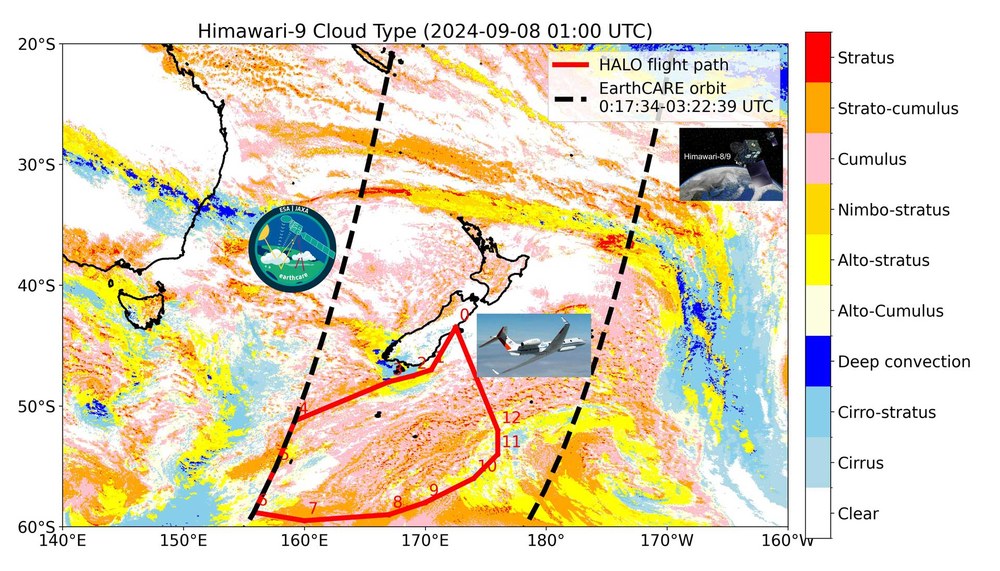

Visualisation – from data and graphic elements from JAXA/EORC, ESA/JAXA, ESA/EarthCARE and DLR – created by Ziming Wang (University of Mainz)

- Together with the Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research, DLR is investigating the interaction between clouds, aerosols and radiation over the Southern Ocean as part of the HALO-South project.

- The researchers aim, among other things, to close knowledge gaps in existing climate models.

- For this, the HALO research aircraft is being used to measure atmospheric particles, trace gases and cloud properties, complementing satellite data.

- Focus: Aeronautics, atmospheric research

How will the atmosphere and clouds react to declining emissions in the coming decades? What aerosols are present over the Southern Ocean and where do they come from? To answer these and other questions, the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) is supporting a group of researchers led by the Leibniz Institute of Tropospheric Research (TROPOS) in the HALO-South mission. Starting in September 2025, the HALO (High Altitude and LOng range) research aircraft will spend 176 flight hours investigating the interaction of clouds, aerosols and radiation over New Zealand – specifically the Southern Ocean. HALO is currently undergoing extensive preparations at DLR’s site in Oberpfaffenhofen for its deployment.

For five weeks, HALO will operate out of Christchurch, New Zealand, carrying out measurement flights over the oceans of the southern hemisphere. Here, around Antarctica, the atmosphere is still relatively clean, giving researchers a glimpse of a lower-emission world. The region is one of the cloudiest on Earth and differs in key ways from the northern hemisphere, which has been more extensively researched for climate models. Due to fewer land masses, lower population density and less industry, the atmosphere here is significantly cleaner than in the north. As such, there are fewer particles to form cloud droplets and ice crystals – meaning fewer clouds expected to consist purely of ice particles or coexisting ice particles and liquid droplets. To date, most climate models have been based mainly on data from the northern hemisphere. For the southern hemisphere, more extensive measurements are still lacking – but the HALO-South project aims to close this gap and provide data for more accurate modelling.

For the first time, the research flights will also measure the number of ice nuclei, in parallel with the number of cloud particles. This is crucial to better understand ice multiplication processes and their impact on cloud formation. The measurements mark the start of a research collaboration between Germany and New Zealand.

Approximately 50 researchers will take part on site: from the Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research (TROPOS), the Leipzig Institute for Meteorology at Leipzig University, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU), Goethe University Frankfurt (GUF), the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry (MPIC) Mainz, the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), the DLR Institute of Atmospheric Physics and the Jülich Research Centre (FZJ). The aircraft will be operated by the DLR Flight Experiments facility. The University of Canterbury in Christchurch and MetService New Zealand will also participate with ground-based measurements.

On the trail of trace gases in the atmosphere

The DLR Institute of Atmospheric Physics is contributing several instruments to HALO-South. Using various detectors, researchers determine the origin and composition of the air masses being studied. "This is necessary to correctly classify the cloud formation processes," explains Helmut Ziereis from the Institute. "The trace gases being studied serve as 'tracers'. Their concentrations and distribution reveal where the air masses come from and the extent to which they have been influenced by natural or anthropogenic – that is, human-made – sources," Ziereis continues.

As more trace gases are measured at the same time, the analysis of the air masses becomes more precise. Each of these gases has its own typical sources. Carbon monoxide, for example, is mainly produced by combustion processes on the ground, such as road traffic or open fires. Nitrogen oxides come from both natural sources, like lightning, and anthropogenic processes, such as air traffic or the combustion of biomass. Methane also has various sources: it is produced naturally in wetlands, among other places, but human activities are the main sources of methane emissions – particularly agriculture and fossil fuel extraction. Ozone is formed in the lower atmosphere through complex chemical reactions, but originates largely from higher atmospheric layers.

"When we look at these gases together, we see a clear pattern – a chemical fingerprint," explains Ziereis. "This allows us to determine where an air mass comes from and which processes have shaped its composition."

HALO measures cloud and aerosol properties

For the measurement flights, researchers equipped DLR's HALO research aircraft with five highly sensitive cloud measuring instruments that record the size, number and shape of cloud particles. "Sensors under the wing and on a windowpane measure particles ranging from approximately one micrometre to six millimetres in size – covering almost the entire size range of natural clouds," explains Christiane Voigt from the DLR Institute of Atmospheric Physics. "Two of the measuring instruments also provide high-resolution images that can be used to determine the phase state – that is, whether the particles are ice or supercooled water droplets."

Additional instruments located both outside and inside the aircraft are used to measure aerosols – tiny particles suspended in the air – and can detect these particles down to ten nanometres in size. The measurements are crucial because aerosols – depending on their size and composition – act as seeds for cloud droplets. Under normal atmospheric conditions, clouds cannot form without aerosols. The HALO aircraft is operated by DLR’s Flight Experiment facility.

Further support comes from the Japanese Himawari weather satellite. Its data is combined with HALO's flight path and provides real-time information on cloud types and aerosol quantities along the route. This allows flight planners to respond directly to current conditions, such as when warm, supercooled or icy clouds form in a region, or when cloud-free areas present opportunities for aerosol measurements.

HALO is being refitted for the mission at DLR’s site in Oberpfaffenhofen until the end of August 2025 and then will be transferred to New Zealand in the first week of September. The first measurement flights are planned for the second week of September, with HALO returning to its home base at DLR by mid-October 2025.

Related links

About HALO

The HALO research aircraft is a joint initiative of German environmental and climate research institutions. HALO was procured with funding from the Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (BMFTR), the Helmholtz Association, the Max Planck Society (MPG), the Free State of Bavaria, the Jülich Research Centre (FZJ), the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) and DLR.

The operation of HALO is supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG), the Max Planck Society (MPG), the German Aerospace Center (DLR), the Jülich Research Centre (FZJ), the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) and the Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research (TROPOS). DLR is both the owner and operator of the aircraft.