Small is the new big

ESA/Science Office

When Sputnik, the first satellite, was launched into orbit in 1958, a new era of spaceflight began. Since then, thousands of other orbiters and probes have followed. Until just a few years ago, it was mainly large satellites that made their way into space – some weighing several tonnes and the size of a small van. For example, the Earth observation satellite Envisat had a mass of 8211 kilograms and a size of 10.5 × 4 × 4 metres at its launch in March 2002.

Continuous technological research has since made it possible to design components and systems for spaceflight ever more efficiently. This has created the opportunity to miniaturise satellite systems such as scientific instruments, control systems and power supplies.

Small satellites – affordable even for smaller budgets

The result is small satellites such as PocketQubes with an edge length of five centimetres, or the ten-centimetre CubeSat cubes. The decisive factor for falling into the ‘small satellite’ category, however, is mass: 500 kilograms is the upper limit. Small satellites have many advantages: they can be produced cost-effectively, quickly and in series. Their compact size and low launch mass are also beneficial when it comes to transport into space. Their comparatively low costs and rapid access to orbit also make them attractive for research institutions and universities, enabling timely on-orbit testing of new space technologies. At DLR, we also plan to test new space technologies in orbit with the CubeSat CAPTn-1 from 2026. The satellite is expected to orbit Earth for approximately two years.

Small complements large

Small satellites can also be used in all the classic application areas of spaceflight: they provide communications and internet connectivity in remote regions, observe Earth's surface and climate, and can serve as subsystems to support primary spacecraft during exploration missions.

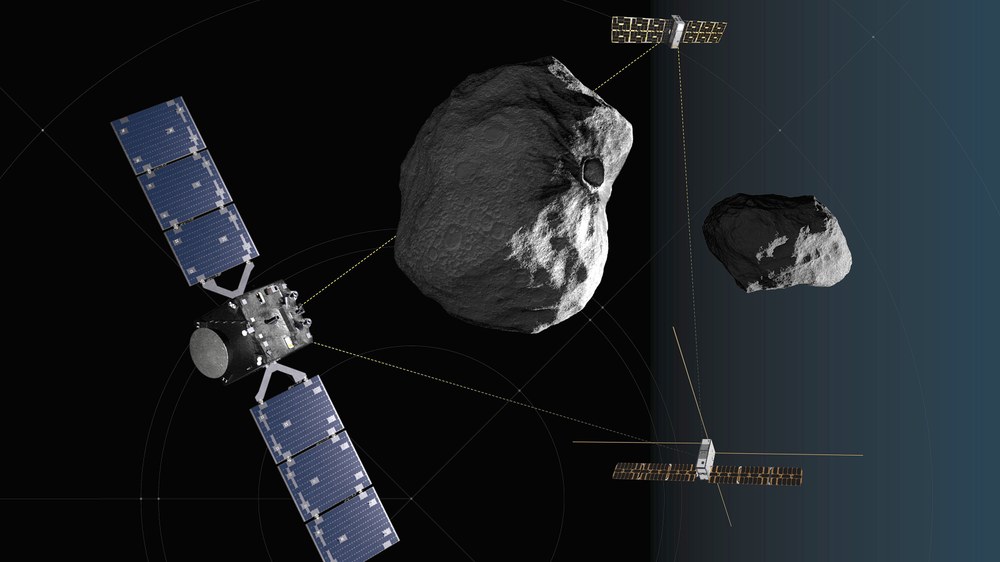

The European Hera mission, which set off in October 2024 for the binary asteroid system Didymos and Dimorphos, is accompanied by the small satellites Juventas and Milani. To find out how asteroids can be successfully deflected, Hera is investigating, among other things, an impact crater on Dimorphos that was created by a controlled collision by NASA’s DART probe. While the large Hera spacecraft is the heart of the mission and carries most of the scientific instruments, the small satellites are used for higher-risk manoeuvres such as landing on the asteroid.

Autonomous driving and precision farming – new tasks for small satellites

Alongside traditional space applications, small satellites are opening entirely new technological possibilities, including in security, transport and Earth observation. Unlike larger satellites, small satellites offer the advantage that many of them can be deployed as a swarm for a single space application, enabling analyses at far shorter intervals. For example, swarms of small satellites can revisit specific regions within an hour, whereas a single satellite might not pass over the same region until the next day at the earliest.

In the transport sector, fleets of small satellites can support new technologies such as autonomous connected driving. The low orbits of small satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) ensure short signal paths and therefore fast response times, while swarm technology provides comprehensive coverage with positioning signals. These signals are used for navigation, control and operation of vehicles. They are highly precise and indicate not only position on a city map but also the respective lane in use and the distance to the kerb and to other vehicles.

The agricultural sector is under immense pressure to produce more with fewer resources. By providing high-resolution, real-time temperature data via small satellites equipped with infrared sensors, the company ConstellR can analyse water consumption and water distribution in fields, for example. This enables farmers to make informed decisions to optimise their sowing, harvesting and use of resources such as water or fertiliser. Thermal information also provides a comprehensive picture of soil and plant health and enables accurate yield forecasts, water optimisation and improved crop profitability.

Thermal infrared measurements from ConstellR's small satellites also help improve the monitoring of river and lake surfaces. Temperature changes in water bodies can indicate increased runoff, inflows or redistribution within the catchment area. In combination with optical and radar data, this enables early detection of flooded areas or expanding bodies of water.

Development of ConstellR's 'Sky-Bee-1' satellite and OroraTech's 'FOREST-3' satellite has been supported through the European Space Agency's InCubed programme. The German Space Agency at the German Aerospace Center (DLR) coordinates funding from the German Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (BMFTR) for the programme.

Small satellites at work in wildfires and cyberattacks

Wildfire detection is another application area for small satellites. Large satellites such as the Sentinels from the European Copernicus Earth observation programme fly over a given region at most once per day. By contrast, the emerging satellite fleet from the start-up OroraTech will, once completed, be able to perform five overflights per day. Its FOREST satellites (Forest Observation and Recognition Experimental Smallsat Thermal Detector) are equipped with a thermal infrared camera and are intended to enable early detection of fires and targeted firefighting. At DLR, we have contributed AI-based analysis methods to the system.

New applications for small satellites are also emerging in security-related tasks in the civil and military sectors. For example, in future, mega-constellations could help safeguard the security of energy grids in Germany: in the context of hybrid warfare, critical infrastructure such as our energy supply has increasingly become a target. Germany's grids are protected by 'redundant' networks, but even these can be disabled. In such cases, CubeSat swarms would then be able to maintain communication within the energy systems, enabling facilities to be brought back into operation, while also increasing security through updates.

In the field of military communications, Europe aims to reduce its dependence on service providers such as the Starlink constellation operated by US company SpaceX. In times of war or crisis, ensuring European sovereignty is essential. Plans therefore call for a major expansion of Europe’s satellite communication systems in the form of small-satellite constellations over the coming years.

From Sputnik to the latest generation of small-satellite swarms, it has been a long journey. Space-based applications have now become indispensable in everyday life. With the ability to test new technologies rapidly and cost-effectively in orbit using small satellites, new developments can proceed even more quickly.